Eikoh Hosoe – Kamaitachi – From Memory to Dream

Leave a commentJanuary 15, 2015 by Rob Cook

Note: This article is not intended to be a detailed history of Hosoe’s life, but more of a homage to the Kamaitachi series. Many important events in the life of Eikoh Hosoe have not been included in this post most notably his relationship with Yukio Mishima. If you ever have a chance to see the full Kamaitachi series don’t miss out. The full work is powerful.

“The camera is generally assumed to be unable to depict that which is not visible to the eye … and yet the photographer who wields it well can depict what lies unseen in his memory.” ~ Eikoh Hosoe

![]() Twenty years ago while teaching English in Japan I made my way to Tokyo to see a show of Eikoh Hosoe’s work. It was a show of current work. After viewing the show I went into the gallery bookstore to see if I could afford anything. I remember looking at one of the original 1000 copies of Kamaitachi in a nice wooden box and wishing I could afford it. I don’t remember the cost, but it was many thousands of yen. That day, one thing I could afford was a simple 4 X 6 inch card in a nice envelope. On the card was mounted a piece of a Hosoe work print. He had torn up work prints into small pieces creating an image from an image. The image I chose looked like it was a piece of an arm from the current work I had just viewed. It was signed and that little piece of art created a bond between Hosoe and me. He has no idea who I am, but, for me, he will always be one of my favorites.

Twenty years ago while teaching English in Japan I made my way to Tokyo to see a show of Eikoh Hosoe’s work. It was a show of current work. After viewing the show I went into the gallery bookstore to see if I could afford anything. I remember looking at one of the original 1000 copies of Kamaitachi in a nice wooden box and wishing I could afford it. I don’t remember the cost, but it was many thousands of yen. That day, one thing I could afford was a simple 4 X 6 inch card in a nice envelope. On the card was mounted a piece of a Hosoe work print. He had torn up work prints into small pieces creating an image from an image. The image I chose looked like it was a piece of an arm from the current work I had just viewed. It was signed and that little piece of art created a bond between Hosoe and me. He has no idea who I am, but, for me, he will always be one of my favorites.

Eikoh Hosoe was born March 18, 1933, in Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture. His father, Yonejiro was a Buddhist priest and his mother, Mitsu a housewife. Hosoe’s family soon moved to Tokyo where he spent his early childhood. In 1944 Hosoe’s family was evacuated back to the countryside where he was born for protection from allied firebombing. A month after the Japanese surrender the family was back in Tokyo. Soon Hosoe was in High School and an active member of the school’s English language club and photographic society. His most common subject matter—the American children who lived in U.S. military housing in a neighborhood built on the ashes of old Tokyo and was called Grant Heights. At the suggestion of a cousin, Hosoe abandoned his given name Toshihiro and adopted “one more suited to the new era”: Eikoh.[i]

Eikoh Hosoe was born March 18, 1933, in Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture. His father, Yonejiro was a Buddhist priest and his mother, Mitsu a housewife. Hosoe’s family soon moved to Tokyo where he spent his early childhood. In 1944 Hosoe’s family was evacuated back to the countryside where he was born for protection from allied firebombing. A month after the Japanese surrender the family was back in Tokyo. Soon Hosoe was in High School and an active member of the school’s English language club and photographic society. His most common subject matter—the American children who lived in U.S. military housing in a neighborhood built on the ashes of old Tokyo and was called Grant Heights. At the suggestion of a cousin, Hosoe abandoned his given name Toshihiro and adopted “one more suited to the new era”: Eikoh.[i]

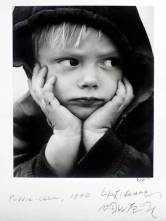

In 1952 the Korean War was raging and the allied occupation of japan had just ended. Nineteen-year-old Hosoe won the top prize for students in the 1952 Fuji Photo Contest for a photograph titled Poddie-Chan. This inspired the young photographer to make photography his life. In 1953 Hosoe viewed an exhibition of works by Edward Weston at the American Cultural Center in Tokyo. He was impressed with how Weston portrayed abstract photographs of trees and seaweed and made them much more than what they were.[ii]

In 1953 after entering the Tokyo Junior College of Photography he formed a connection with the renowned artist Ei-Q, who organized Demokrato, an avant-garde artist’s group. Through this relationship, Hosoe cemented his individualistic way of thinking, which challenged common conceptions of art. [iii] Speaking about his early days in photography, Hosoe said:

I was the restless sort of youth and could never accept the limits that society placed on me. I wanted to do things that nobody else was doing. Failing at something that other people can do was embarrassing to me, but I didn’t see anything embarrassing about failing at things that nobody else was doing. I was a quirky young man, full of nothing but curiosity. This side of my character is reflected in my early photography.[iv]

After graduating fom college, Hosoe worked as a freelance photographer struggling to make ends meet. In 1955 he wrote a  book called “35mm Photography.” The book found success and allowed Hosoe to travel to Shikoku Island and Kobe and Osaka photographing the post war new Japan.[v]

book called “35mm Photography.” The book found success and allowed Hosoe to travel to Shikoku Island and Kobe and Osaka photographing the post war new Japan.[v]

In 1956 Hosoe published a one-man show titled “An American Girl in Tokyo.” The success of that show brought new work and new opportunity to Hosoe.

In 1956 Hosoe published a one-man show titled “An American Girl in Tokyo.” The success of that show brought new work and new opportunity to Hosoe.

In 1962 Hosoe married his first wife, Misako and had his first child, Kenji in 1963. In 1972 Hosoe traveled to San Francisco where he met Jack Welpott and Judy Dater. They introduced him to Cole Weston, the son of Edward Weston. Hosoe convinced Cole to allow him to translate Edward Weston’s book, Daybook of Edward Weston” into Japanese.[vi]

In 1975 Hosoe became a Professor at Tokyo College of Photography where he opened a gallery dedicated to fine art photographs from all over the world.

Early on Hosoe became interested in dance and began his long history of photographing Japanese dancers. This explosive potential became evident for Hosoe one night in I959, at an unprecedented performance called Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors). Onstage was a single male dancer and a live chicken. Watching in the audience was a noted author from whose book the title of the performance was taken, and a young photographer, whose previous subjects had included modern dancers. As the piece reached its conclusion, the dancer, Tatsumi Hijikata, broke the neck of the chicken spilling blood on the stage. Yukio Mishima the author, applauded vigorously and Eikoh Hosoe rushed backstage to meet the dancer. Thus did the first and only performance of Kinjiki end—a landmark in the early history of Butoh dance and the starting point for Hosoe’s long friendship with Hijikata.[vii] Photography and dance became one for Hosoe and held equal places in the creation of art. Hosoe said, “Between photographer and dancer, who moves whom—the cooperative relationship—is not so clear. The beauty of my approach is that the photographer and his subject neither pair off against one another nor coalesce. The finished product is all my own.”[viii]

In 1966 Hosoe began his project, Kamaitachi. For years Kamaitachi was a mystery to me. I knew I loved many of the individual images but they didn’t make sense to me as a group. This past year I was finally able to understand the power of this work after receiving a copy as a gift.

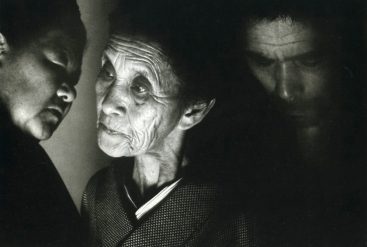

As a child growing up in the Japanese countryside during the early years of what would become the Second World War, Hosoe heard the tales of the yōkai—the strange beings and supernatural creatures who haunt Japanese folklore. What child wouldn’t be a bit frightened by stories about yuki-onna, the snow woman or the mischievous kitsune, the fox, or the invisible kamaitachi. Kamaitachi are weasel like creatures with a sharp sickles in place of each arm. They moved so quickly they’ve never been clearly seen. These clever and arbitrarily vicious creatures traveled on the wind. Humans unlucky enough to encounter kamaitachi were subject to inexplicable pain and suffering.[ix]

As a child growing up in the Japanese countryside during the early years of what would become the Second World War, Hosoe heard the tales of the yōkai—the strange beings and supernatural creatures who haunt Japanese folklore. What child wouldn’t be a bit frightened by stories about yuki-onna, the snow woman or the mischievous kitsune, the fox, or the invisible kamaitachi. Kamaitachi are weasel like creatures with a sharp sickles in place of each arm. They moved so quickly they’ve never been clearly seen. These clever and arbitrarily vicious creatures traveled on the wind. Humans unlucky enough to encounter kamaitachi were subject to inexplicable pain and suffering.[ix]

For Hosoe the kamaitachi series ties together many of Hosoe’s childhood memories. Not just the Japanese countryside and the native folklore—these images also symbolize the awareness that things you can neither see nor understand can, without warning, blow into your life on the wind and leave you unaccountably writhing  helplessly in pain.[x]

helplessly in pain.[x]

In the 2009 edition of Kamaitachi, Hosoe wrote the afterward. I think it is best left to Eikoh Hosoe himself to represent Kamaitachi in his own words:

“For me, Kamaitachi holds the deepest of memories. In my eyes, Kamaitachi means Tatsumi Hijikata. For the twenty-seven years that I knew Hijikata, I continued to receive stimulation, shock, and courage from him, underwritten by an unwavering friendship . . . .

The I950s and I960s brought great change to Japan. As a nation, we were slowly coming to our feet out of the wreckage that surrounded us immediately after the war. Young men like me wanted to grow up fast. We were part of the so-called Beat Generation and found ourselves up against a brick wall of poverty and changing traditions. We were willing to try anything new . . . We wanted to explore how traditional documentary photography and personal expression could be combined.

In 1965, I got the idea to try to photograph an important memory of mine. During the war, I was evacuated from my home in Tokyo to the Tohoku countryside, and I lived there from September 1944 to September 1945. Before evacuating to the countryside, my family and I struggled through hard times, suffering from food shortages and sleeplessness brought on by nightly air-raid sirens and the American bombs. Almost every night, Tokyo and other major cities were devastated, and millions of seniors, women, and children were killed; few young men perished in this way because they had already been drafted. Then on August 6, 1945, in Hiroshima and three days later in Nagasaki two atomic bombs were dropped. This great tragedy has remained with me as a spiritual trauma. Although I was a young boy, twelve years old, when it happened, I remembered this period vividly—as a dark time but also as a uniquely free time. Against the backdrop of this larger, terrible history, I found I had fond memories of a mischievous young boy happy to be playing in the countryside.

In 1965, I got the idea to try to photograph an important memory of mine. During the war, I was evacuated from my home in Tokyo to the Tohoku countryside, and I lived there from September 1944 to September 1945. Before evacuating to the countryside, my family and I struggled through hard times, suffering from food shortages and sleeplessness brought on by nightly air-raid sirens and the American bombs. Almost every night, Tokyo and other major cities were devastated, and millions of seniors, women, and children were killed; few young men perished in this way because they had already been drafted. Then on August 6, 1945, in Hiroshima and three days later in Nagasaki two atomic bombs were dropped. This great tragedy has remained with me as a spiritual trauma. Although I was a young boy, twelve years old, when it happened, I remembered this period vividly—as a dark time but also as a uniquely free time. Against the backdrop of this larger, terrible history, I found I had fond memories of a mischievous young boy happy to be playing in the countryside.

So I decided to record the Tohoku area, specifically the northeast portion, which was, as it turned out, the birthplace of both Hijikata and myself. In the mid-1960s, Japan, especially its

So I decided to record the Tohoku area, specifically the northeast portion, which was, as it turned out, the birthplace of both Hijikata and myself. In the mid-1960s, Japan, especially its

countryside, was evolving rapidly. I was afraid that this rural region from my memories would be totally transformed, becoming nothing but flat and faceless terrain—a victim of

modernizatih the land before it is changed irrevocably,but how?” I had decided I did not want to be a traditional documentary photographer (recording a place and its people directly). I was a much greedier photographer than that: I wanted to capture my memory of the land from which my mother came and where I was born.

One thing I remembered from my days as a kid in that countryside was a sinking feeling we

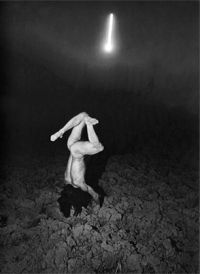

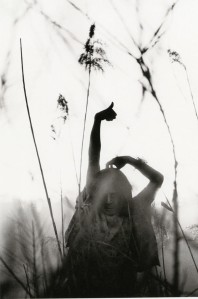

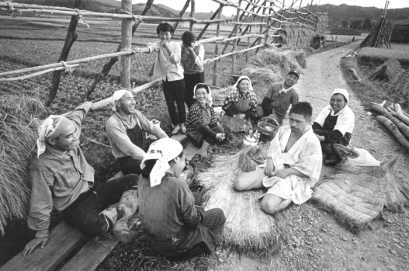

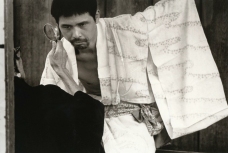

sometimes had, as though something terrible would happen if we dared to venture outside after dark. The fields seemed to be full of ghosts and demons some of them romantic, some of them awful. Kamaitachi was one of the more terrifying ones: an  invisible, tiny, weasel Iike beast that would slash at farmers in the field. (Kama means ”sickIe” and itachi means ”weaseI.”) Between I965 and I968, Hijikata and I visited several villages around Tohoku, improvising a performance of sorts against the backdrop of traditional village life in an effort to create a subjective documentary of our youth. We also continued working together in Tokyo during this time. The images of those I photographed in Tokyo were my memories of life before I was sent to the countryside to avoid the air raids. When we traveled to the farmlands, the villagers we came in contact with became the people in my memories from the time of my evacuation. Hijikata always played the role of the trickster kamaitachi, and every now and then I’d ask him to perform specific actions—interacting with the locals or suddenly running across the fields. One very cold night, under a full moon, I asked him to get undressed and lie down on the bed of a dry rice paddy. How patient he was! Kamaitachi is a record of my own nostalgia and sadness for my schoolboy evacuation, but it is also a record of Tatsumi Hijikata. It is a ”record of a record,” making this an extremely unique work.

invisible, tiny, weasel Iike beast that would slash at farmers in the field. (Kama means ”sickIe” and itachi means ”weaseI.”) Between I965 and I968, Hijikata and I visited several villages around Tohoku, improvising a performance of sorts against the backdrop of traditional village life in an effort to create a subjective documentary of our youth. We also continued working together in Tokyo during this time. The images of those I photographed in Tokyo were my memories of life before I was sent to the countryside to avoid the air raids. When we traveled to the farmlands, the villagers we came in contact with became the people in my memories from the time of my evacuation. Hijikata always played the role of the trickster kamaitachi, and every now and then I’d ask him to perform specific actions—interacting with the locals or suddenly running across the fields. One very cold night, under a full moon, I asked him to get undressed and lie down on the bed of a dry rice paddy. How patient he was! Kamaitachi is a record of my own nostalgia and sadness for my schoolboy evacuation, but it is also a record of Tatsumi Hijikata. It is a ”record of a record,” making this an extremely unique work.

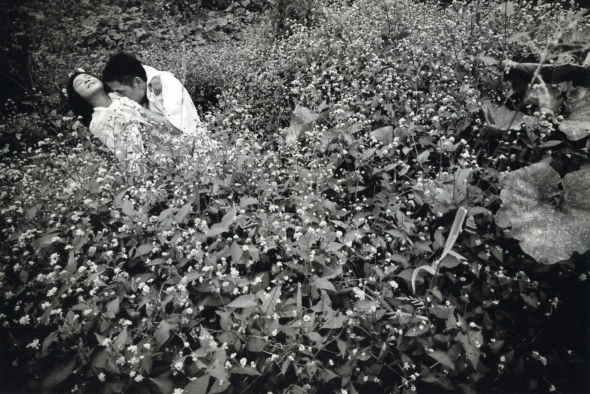

As the series evolved, it became a kind of collaboration between me, Hijikata, and the villagers who participated in our shenanigans. Later on, I felt I probably owed an apology to those people, who must have been surprised when these two young men appeared out of nowhere and inserted themselves into their daily lives and rituals, snatching babies from cribs and shouting over their shoulders, ”Sorry, we’re just borrowing your baby for a few seconds!” In our performances, we became, for just

As the series evolved, it became a kind of collaboration between me, Hijikata, and the villagers who participated in our shenanigans. Later on, I felt I probably owed an apology to those people, who must have been surprised when these two young men appeared out of nowhere and inserted themselves into their daily lives and rituals, snatching babies from cribs and shouting over their shoulders, ”Sorry, we’re just borrowing your baby for a few seconds!” In our performances, we became, for just  a moment, two kamaitachi. June 2009”[xi

a moment, two kamaitachi. June 2009”[xi

Hosoe shot the series initially in Hijikata’s hometown Akita, then later in Shibamata and Sugamo in Tokyo. In the Forward of the second edition of Kamaitachi, Hosoe, described how he photographed, “In the village, he played with children, was laughed at by farmers along the roadside, sat in the middle of a field, attacked a bride, kidnapped a baby, and ran through the rural landscape. Almost all the shooting was done guerrilla style in a flash. This was something that could only be achieved through photography. No other medium — film, television, painting, or novel — could have been used in its place. At that moment, I was certain of the superiority of photography.” The series was published as a book in 1969 with only 1000 signed copies being produced. For Hosoe and Hijikata, Kamaitachi was a performance of dreams and memories.

Today, Eikoh Hosoe is deeply involved in photography education. He is the director of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, whose stated goal is the support and encouragement of young photographers. In an interview for ko-e magazine, Hosoe explained his philosophy on photography:

Today, Eikoh Hosoe is deeply involved in photography education. He is the director of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, whose stated goal is the support and encouragement of young photographers. In an interview for ko-e magazine, Hosoe explained his philosophy on photography:

“My basic theory is “photography is art that is about the relationship between the subject and the photographer.” The photographer can impose his subjective interpretation of the subject … the more blurred this is, the more interesting the result. Whatever the case, the photographer is but a mediator. Whether he leans more toward objective or subjective expression, the photographer is absolutely responsible for the finished product. This is the reason why copyrights exist and why they apply to all photographs. This is the case for news photographs that stress objectivity as well as for artistic ones that value the artist’s guiding hand. The dearest photographs are the ones that act as memory because memories can never be remade. But photographs are not just there for the sake of memory. Photography is an important art form.”[xii]

In the hands of Eikoh Hosoe, photography is a performance and the photographic image a work of art. He constantly pushes the boundaries in all that he does. His resulting enduring life’s work speaks for itself.

Works Cited

[i] “Sunday Salon with Greg Fallis, Eikoh Hosoe.” [Online] Available < http://www.utata.org/sundaysalon/eikoh-hosoe/>

[ii] “Photography Influence Eikoh Hosoe.” [Online] Available < http://photographyinfluences.blogspot.com/2009/04/eikoh-hosoe.html>

[iii] “Let’s Visit Eikoh Hosoe’s Exhibition “Kamaitachi.” [Online] Available <http://www.meetup.com/TokyoPhotographyLovers/events/189126152/

[iv] “Hosoe Eikoh – Interview ko-e Magazine.” [Online} Available http://www.koemagazine.com/2010/01/hosoe-eikoh/

[v] Photography Influence Eikoh Hosoe.

[vi] Photography Influence Eikoh Hosoe

[vii] Ronald J Hill [Afterward] Eikoh Hosoe. The Friends of Photography, 1963.

[viii] Hosoe Eikoh – Interview, ko-e Magazine.

[ix] Sunday Salon with Greg Fallis, Eikoh Hosoe

[x] Sunday Salon with Greg Fallis, Eikoh Hosoe

[xi] Eikoh Hosoe: Kamaitachi. New York: Aperature Foundation, 1969, 2005, and 2009.

[xii] Hosoe Eikoh – Interview, ko-e Magazine.