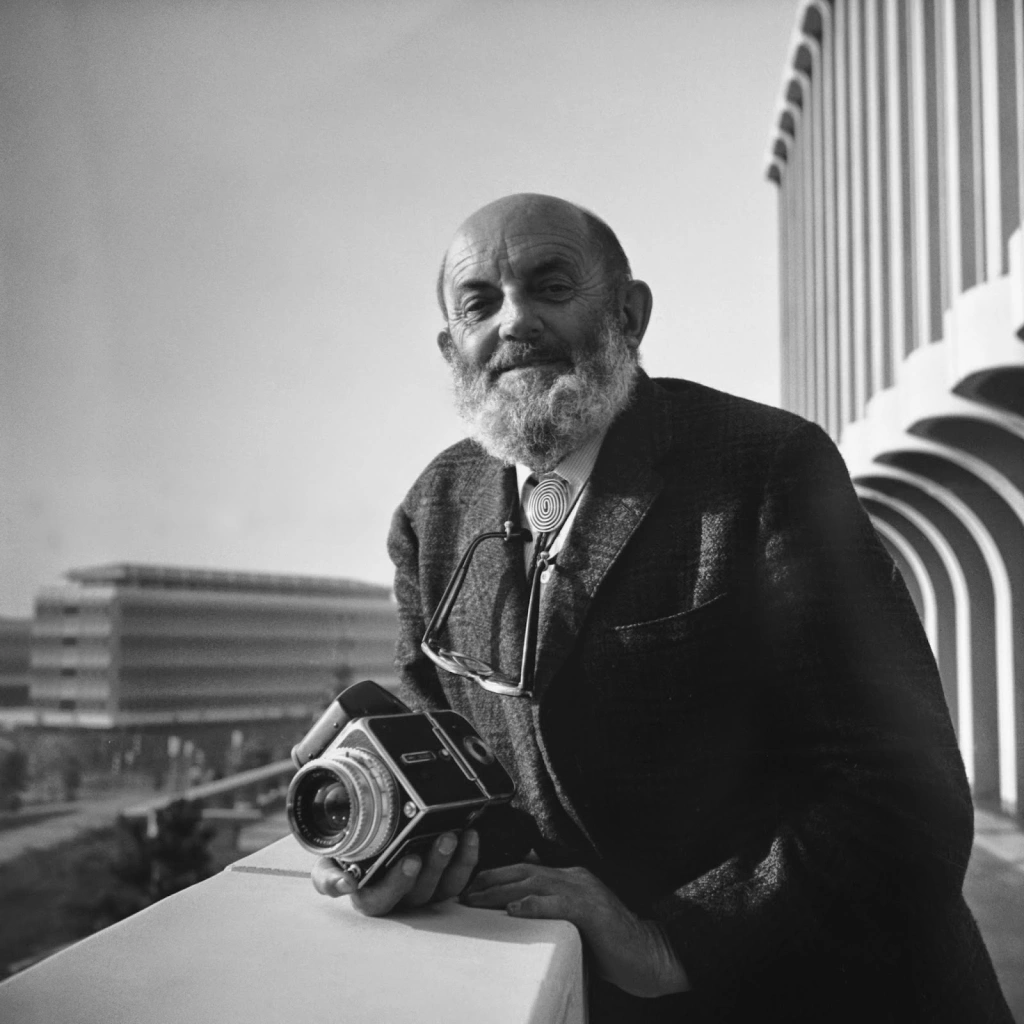

Ansel Adams – A Beautiful Life

Leave a commentAugust 20, 2022 by Rob Cook

Styling Changes

Imagination is the offspring of change. It’s been two years since my last post on Edward Curtis, and WordPress has changed. WordPress now adds a space in between paragraphs in quotes. The theory is that the reader won’t stay focused on long blocks of text, and it is visually pleasing to the eye to have white space; I believe both theories are correct. The problem is that it is incorrect style formatting. So, when reading this post, try to imagine the quotes are in the correct style.

Author’s Note

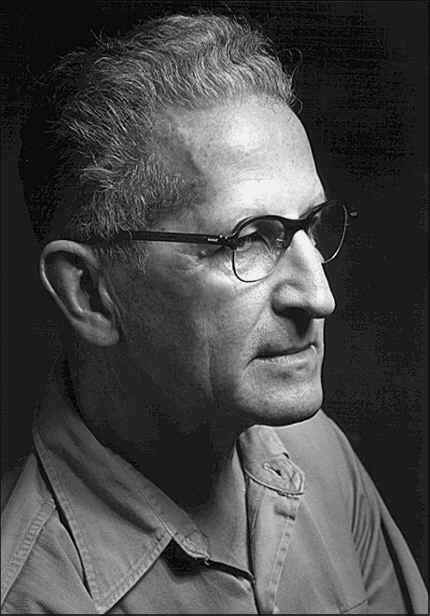

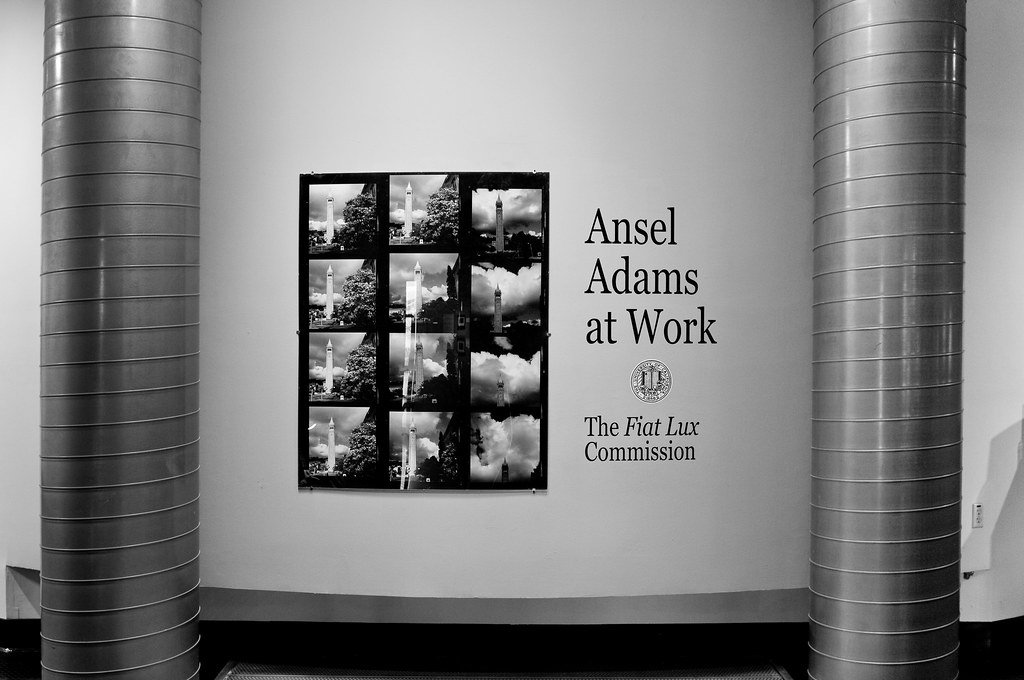

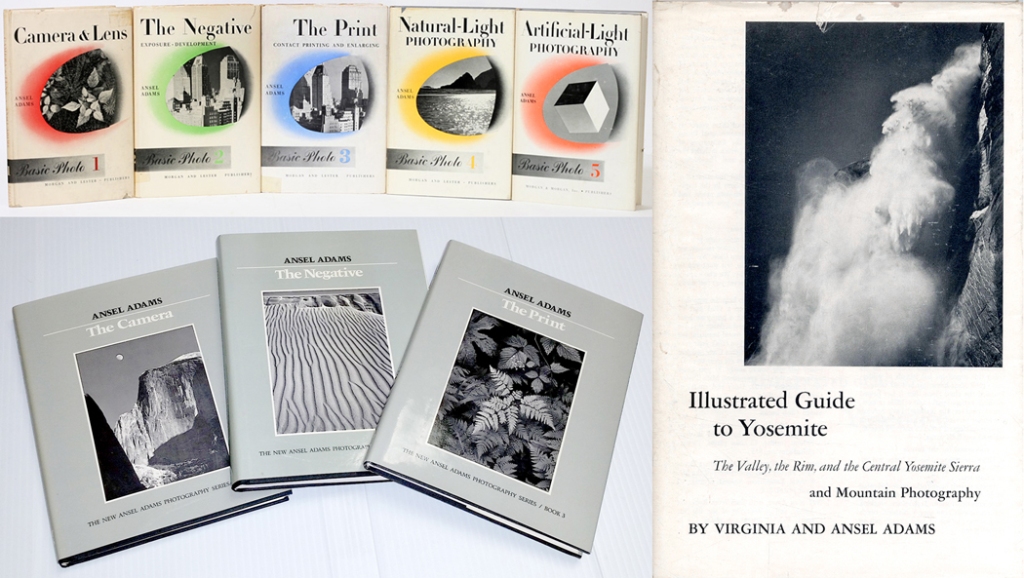

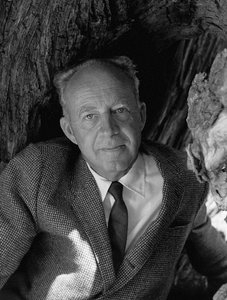

The amount of information available on Ansel Adams is staggering. In this post, I have drawn heavily on the research and writings of Mary Street Alinder and Ansel himself. If you are interested in Ansel Adams, I would strongly suggest beginning with Mary Street Alinder’s phenomenal biography of Ansel titled Ansel Adams A Biography. Mrs. Alinder is the quintessential expert on the writings, life, and work of Ansel Adams. Another essential source is Ansel’s Autobiography. The best early history of Ansel is Nancy Newhall’s book, Ansel Adams: Eloquent Light. Another important source is Andrea G Stillman’s, Looking at Ansel Adams: The Photographs and the Man. Both Andrea Stillman and Mary Alinder were personal assistants to Ansel and knew him the best; look for their books. You won’t regret it.

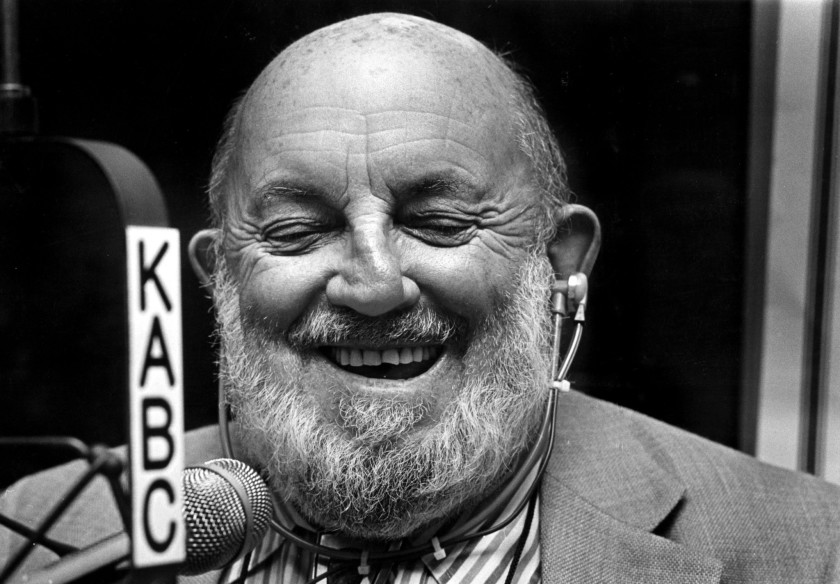

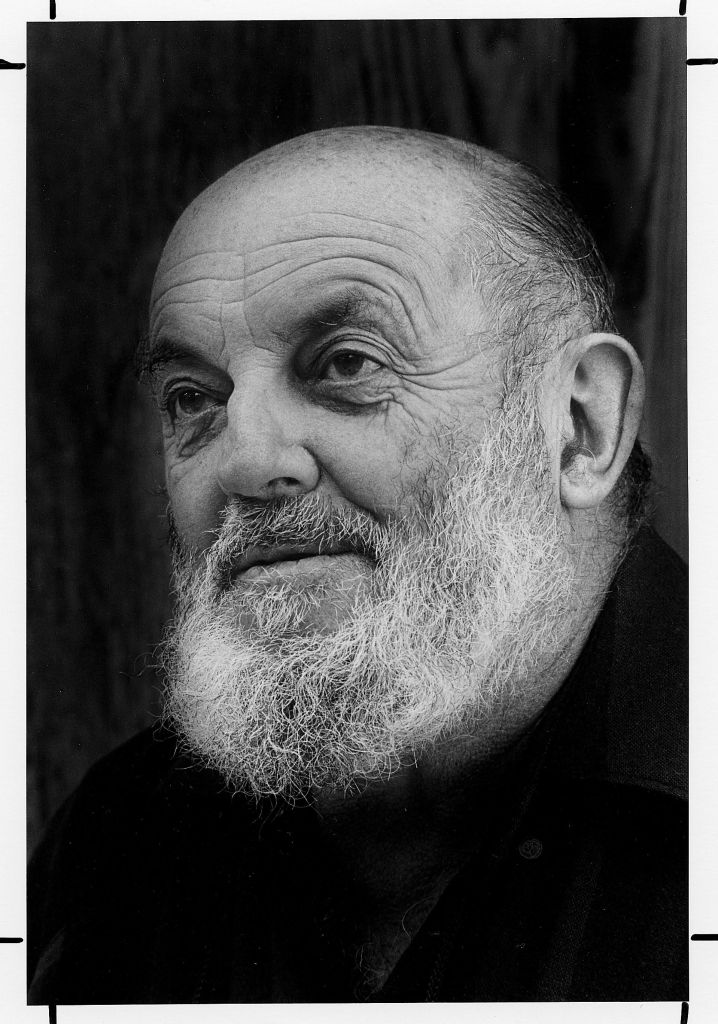

Ansel Adams

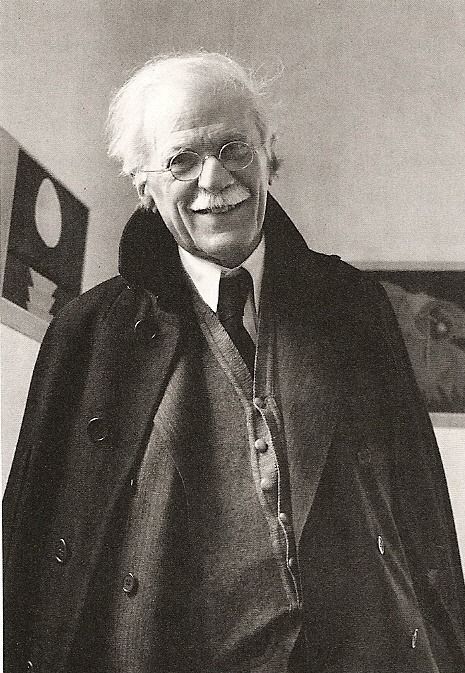

I had no idea the enormous impact Ansel Adams had on modern photography. He has never been one of my favorites; I just didn’t get him or his work. I felt he was too commercial. When I was studying photography in the early 1980’s numerous Ansel Adams books, calendars, and posters saturated the market, his work was everywhere. I just did not look close enough at his images. I preferred the documentary style of W. Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and John Thompson. After researching this post, I discovered I had been missing out; I was ignoring a great photographer and man.

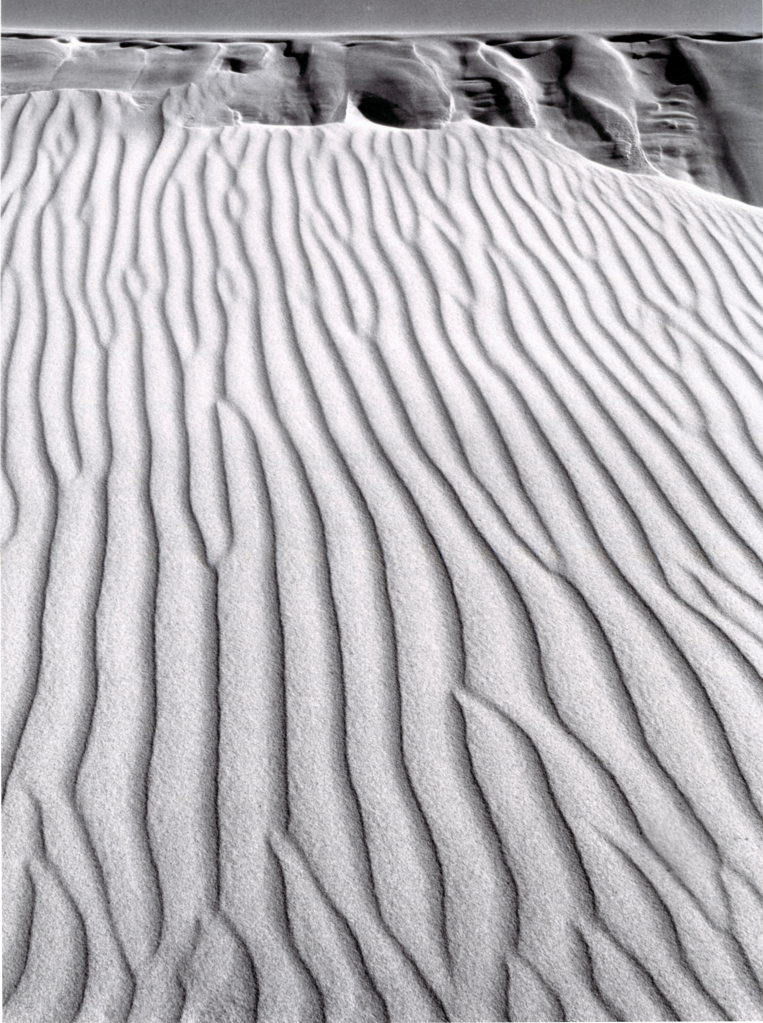

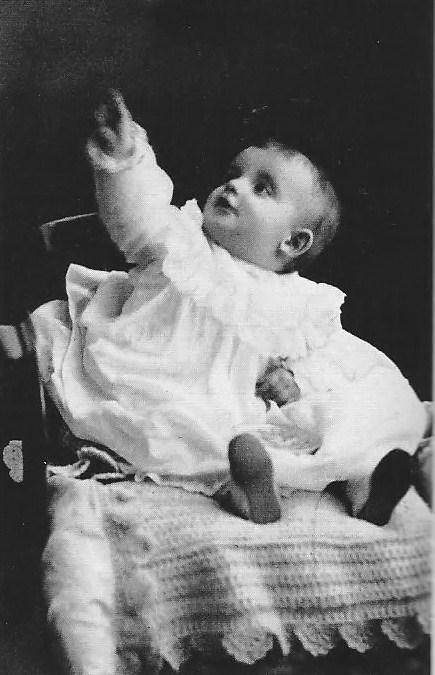

Ansel Easton Adams was born in San Francisco, California on February 20, 1902. The following year his family moved to the dunes beyond the Golden Gate.[1] Ansel’s earliest memories were of the dunes and watching the fog roll in.[2] In a quote from his autobiography, he describes his memories and the foundation they were for his love of nature:[3]

Memories come to me as if they are scenes revealed by the stately opening of a proscenium curtain. A spring morning in about 1910 came clearly to me. I was up early and out in the dunes near our home. A gale blew out of the northwest, difficult to stand against. It was cold and clear, and the grasses and flowers were shivering violently in their shallow little spaces above the ground. The brittle-blue distances, including the horizon of the sea, were of crystal incisiveness. The ocean was flecked with whitecaps that appeared as countless white threads in a blue tapestry. My experience that day was a form of revelation that in some way became part of my creative structure.

I constantly return to the elements of nature that surrounded me in my childhood, to both the vision and the mood. More than seventy years later I can visualize certain photographs I might make today as equivalents of those early experiences. My childhood was very much the father to the man I became.[4]

1906 San Francisco Earthquake

The morning of April 18th, 1906 was peaceful and quiet in the Adams’ household; it was still early. At 5:12 am, a distant rumble started, and one of the most pivotal events of Ansel Adam’s life was about to be unleashed. The house began to gently sway, quickly turning violent. Four-year-old Ansel and his nanny were thrown from wall to wall, and the windows in Adams’ home shattered. The noise was deafening. Mary Street Alinder, in her biography of Ansel, describes the scene:

After seventy-five seconds of terror, it stopped. The violent release of pent-up energy had displaced the earth up to twenty-one feet, with a force measuring 8.25 on the Richter scale . . . San Francisco was in shambles and on fire thanks to exploding gas mains.

Ansel’s mother, Olive pulled herself together and surveyed the wreckage. She found they had been very lucky: one chimney missing, two fireplaces and the greenhouse lost, the plaster walls riddled with cracks, and woodwork hanging wildly from walls, but everyone was alive.[5]

In his Autobiography, Ansel had vivid memories of the events of those days:[6]

I was a little over four years of age and was very curious, wanting to be everywhere at once. There were many minor aftershocks, and I could hear them coming. It was fun for me, but not for anyone else. I was exploring in the garden when my mother called me to breakfast, and I came trotting. At that moment a severe aftershock hit and threw me off balance. I stumbled against a low brick garden wall, my nose making violent contact with quite a bloody effect. The nosebleed stopped after an hour, but my beauty was marred forever – the septum was thoroughly broken. When the family doctor could be reached, he advised that my nose be left alone until I matured; it could then be repaired with greater aesthetic quality. Apparently, I never matured, as I have yet to see a surgeon about it.

The impressions of confusion during the following days and, above all, the differences in daily life, are still very much with me.

Ansel’s father, Charles Adams, franticly tried to get to his family. He was on the East Coast conducting business, and the information he was receiving was spotty and inaccurate at best. The train West stopped in Reno, where he received a telegram from Olive’s father assuring him the family was safe.[7] Ansel said:

I now can understand the intense anxiety my father must have felt, thousands of miles away, buffeted by outrageous telegraphed rumors of total disaster. It had been variously reported that all of the city had burned; that San Francisco was slowly sinking into the sea, or that a huge tidal wave had wrecked the entire Bay area. My father left Washington as soon as he could find space on a train and arrived about six days later. Finally reaching the ferry docks, he was unable to get a horse and buggy, so he ran and walked five miles around the periphery of the fire to our home. Happily, he found all was well. His family was healthy and the house they had built was largely intact.

My closest experience with profound human suffering was that earthquake and fire. But we were not burned out, ruined, or bereft of family and friends. I never went to war, I was too young for the first and too old for the second. My world has been a world too few people are lucky enough to live in – one of peace and beauty. I believe in beauty. I believe in stones and water, air and soil, people and their future, and their fate.[8]

Unusual Squirrel

Ansel Adams was an odd little child. He describes himself as a “repellent little brat.”[9] Despite a slight frame, he was blessed with enormous stamina. “As a child, I was prone to frequent illness; I had extremely poor teeth that plagued me later in life.[10]”

He was extremely unhappy, grew emotionally unstable, and cried easily.[11] Nancy Newhall, in her biography, The Eloquent Light describes Ansel:

He was a strange, intense, and thorough child. Whatever, he began, he saw through to its finish. As a baby, building castles and cathedrals with the marvelous architectural German blocks of the time, he carefully completed his great structures through several days, and then, just as carefully, put all the blocks back in their box in precisely their original positions. He was an odd-looking boy, very thin, and fast. Indeed, with the wide dark eyes, swollen nose, and slightly open mouth. He possessed a vivid imagination: he suffered from nightmares, delighted in comedy and fantasy, and was profoundly moved by beauty.[12]

Spurred by an enormous curiosity and a restless intelligence, Ansel was drawn to any precise or complicated instrument. He listened intently while his father explained the immensities of the universe, and his telescope showed him the moon, a planet, a comet, or the bright cluster of the Pleiades.[13] When he began a project, he would not rest until he made it a reality.[14] In grammar school, as a kid, he was considered ’unusual”—not in his right mind, so to speak. The fact that he could do many things deftly and never was a bad little boy was not sufficient to overcome the stronger fact that he was ”different.”[15]

Though not lacking in self-confidence, he was a lonely child.[16] More comfortable with adults, he had few friends; He looked like a skinny squirrel, with eyes that bulged a bit and ears that stuck out. These features, combined with his twisted nose and open mouth— whether for breathing or to allow for his almost constant chatter—made him seem strange to other children.[17]

He was always in motion; otherwise, he would twitch with frustration, his mind flitting along with his body. He ran everywhere. He was impatient at the tempo of walking and the slow sidewalk flow of pedestrians, and he simply ran, doubtless an object of curiosity.[18] He had no patience for games; today he would probably be diagnosed as ADHD. Back then, he was seen as a significant behavior problem.”[19]

Education

Formal education for Ansel was difficult; he had little interest in book learning. In his autobiography, he says:

Each day was a severe test for me, sitting in a dreadful classroom while the sun and fog played outside. Most of the information received meant absolutely nothing to me. For example, I was chastised for not being able to remember what states border Nebraska and what are the states of the Gulf Coast. It was simply a matter of memorizing the names, nothing about the process of memorizing or any reason to memorize. Education without either meaning or excitement is impossible. I longed for the outdoors, leaving only a small part of my conscious self to pay attention to schoolwork.

One day as I sat fidgeting in class the whole situation suddenly appeared very ridiculous to me. I burst into raucous and uncontrolled laughter; I could not stop. The class was first amused, then scared. I stood up, pointed at the teacher, and shrieked my scorn, hardly taking a breath in between my howling paroxysms. To the dismay of my mother, I was escorted home and remained under house arrest for a week until my patient father concluded that my entry into, yet another school would be useless. Instead, I was to study at home under his guidance.[20]

Ansel’s father decided it was best to take the boy out of school and educate him on his own. In the early 1900s, the concept of homeschooling was unique. Public schools in those days were not equipped to handle gifted children.[21] Charles Adams was quite prolific in French and taught Ansel basic concepts of algebra. He insisted Ansel read the English classics and provided his son with a tutor to teach Greek culture and language.[22] His favorite hobby was collecting insects.

Music

One day when Ansel was about 12, his father heard him trying to pick out notes on their old upright piano. He decided that his son had talent! Ansel soon began piano lessons, which were in addition to his other studies.[23] Mary Street Alinder wrote:

Ansel’s mother bought her son a book of piano music, and he immediately sat down at the keyboard and taught himself to read music and play. His father wrote in 1914 that it happened almost overnight.Until he was seventeen or so, Ansel was possessed of a so-called photographic memory: he could look briefly at a page of text, or music, and then recite it. This was of great value in his musical studies. Always convinced that Ansel was special, his father now knew he was a prodigy.[24]

Ansel dove headfirst into music. It became his haven against the chaos of life. Music was a place where he could feel the passions and emotions that surged inside him; until then, his life had seemed aimless and confused. But realizing that he could create beauty through the piano, he found his first unmediated link to the eternal.[25] Music provided Ansel with a structured approach to life, and it gradually changed him from being a hyperactive brat to a disciplined artist. This discipline was life-changing. He became determined to make music his career; his goal was to become a classical pianist. He studied hard and soon became quite accomplished. In a letter to Ansel’s grandmother, Charles Adams describes the genius his son had within.

Ansel has developed quite a taste for music lately. He started a few months ago to play on the piano and heaven knows where it comes from, but he can read almost anything put before him at sight. Four months ago, he didn’t know a note and of course, has never taken lessons so I can’t quite understand it.[26]

Music had a great impact on Ansel’s life. It was through his study of music that he gained his best friends, including Cedric Wright, who would become his link to another form of expression, photography.

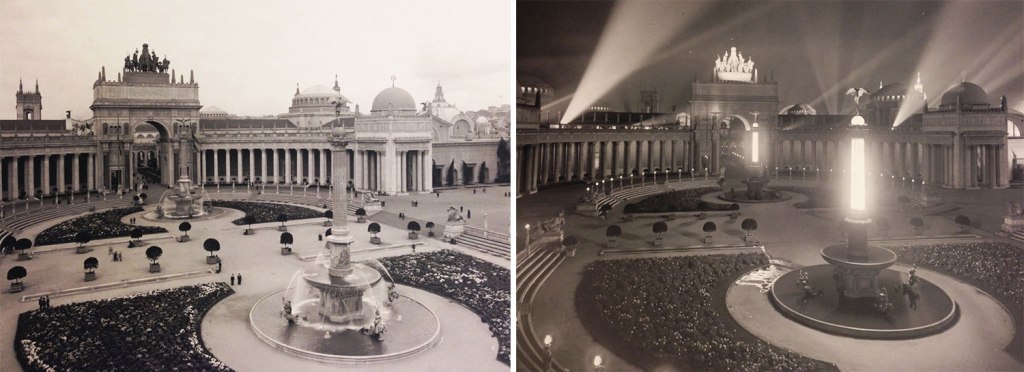

Panama-Pacific International Exposition

In 1915, Charles Adams presented Ansel with an unusual present: a one-year pass to San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition, scheduled to open on Ansel’s thirteenth birthday. This and his musical studies were to constitute his schooling for the year.[27]

In her biography of Ansel, Mary Street Alinder describes his experiences at the Exposition:

The Exposition celebrated San Francisco’s recovery from the earthquake and fire . . . It was a spectacle, boasting not only the latest achievements in industry, science, and the arts but also an amusement park called the Zone, just the thing for a very active thirteen-year-old. There was a roller coaster, a carousel, a huge trampoline, and the Auroscope, a large car that carried its passengers 285 feet above the ground. Ansel attended lectures and thought nothing of rising to ask questions of the learned speakers. Thanks to his regular visits and his enormous curiosity (with its accompanying stream of questions), Ansel became known to many of the exhibitors.[28]

Ansel was a daily participant in the fair. His father would drop him off every morning on his way to work and meet him in the afternoon, sometimes going to the exhibits together. A few times, Ansel’s mother and aunt went with him. Ansel describes his memories in his autobiography:

The exposition was large, complex, and astounding: a confusion of multitudes of people, more than I had ever encountered, with conversations at excitement levels and innumerable things to see. I visited every exhibit many times during that year.

In some respects, it was a tawdry place, a glorious and temporary stage set, a symbolic fantasy, and a dream world of color and style. The buildings, constructed expressly for the exposition, were huge and flamboyant, with great scale and spaciousness. And then there was the Zone, the amusement area. In addition to the usual neck-breaking rides, tumblers, twisters, and tunnels of love, there were the seamy traps of girlie shows, curio shops, and freak displays.

The Festival Hall, a huge, domed building with excellent acoustics, contained an organ. We would have something to eat at the YMCA cafeteria and stay for the fireworks; they were always spectacular.

Although everyone at the exposition was kind to me, I am sure I was a real pest. Exhibitors seemed interested in inquisitive children and went out of their way to explain things.[29]

Many days Ansel would play the piano in the Nevada Pavilion, often to standing room only crowds.[30]

Little did Ansel realize the effect that year of exploration would have on his life. In addition to the scientific and cultural displays, he was exposed to the great art of human history. Names like Van Gough, Renoir, and Monet were displayed. Among the exhibits were three photographs by Edward Weston and several by Imogen Cunningham, who would become Ansel’s life-long friends.[31]

After the exposition ended, Ansel returned to the classroom, floating from school to school, ultimately ending up at the Wilkins school. The patient headmistress read the lessons out loud to Ansel, giving him an A and allowing him to graduate from the eighth grade; this ended his formal education.

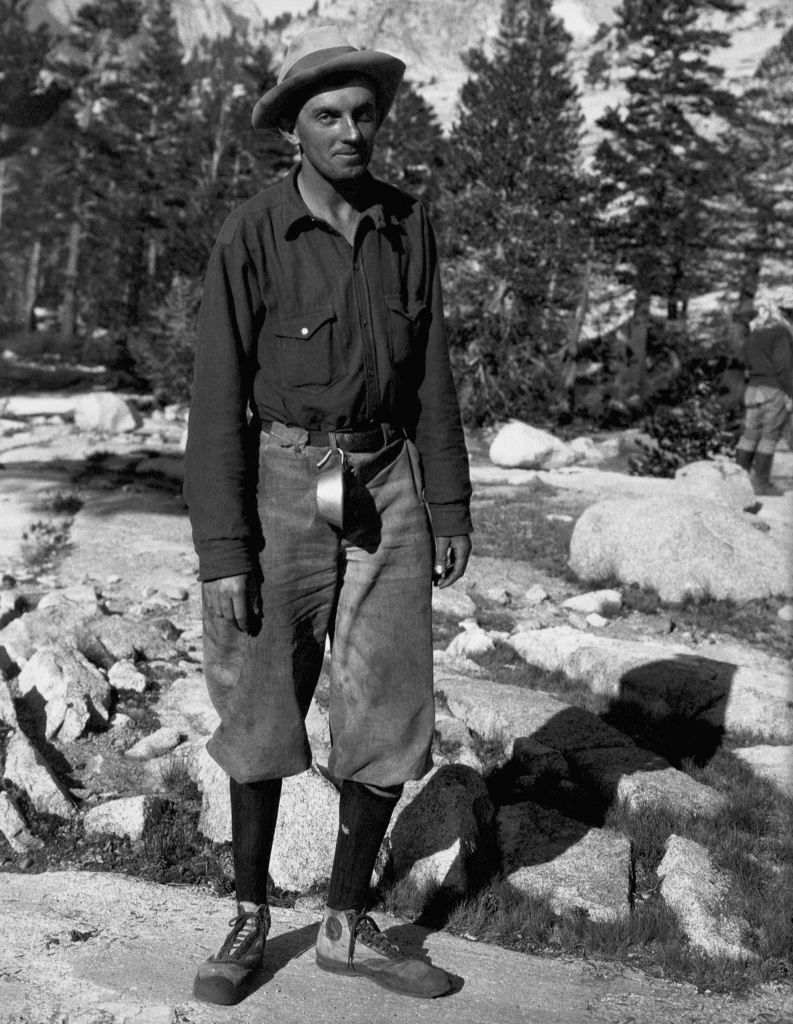

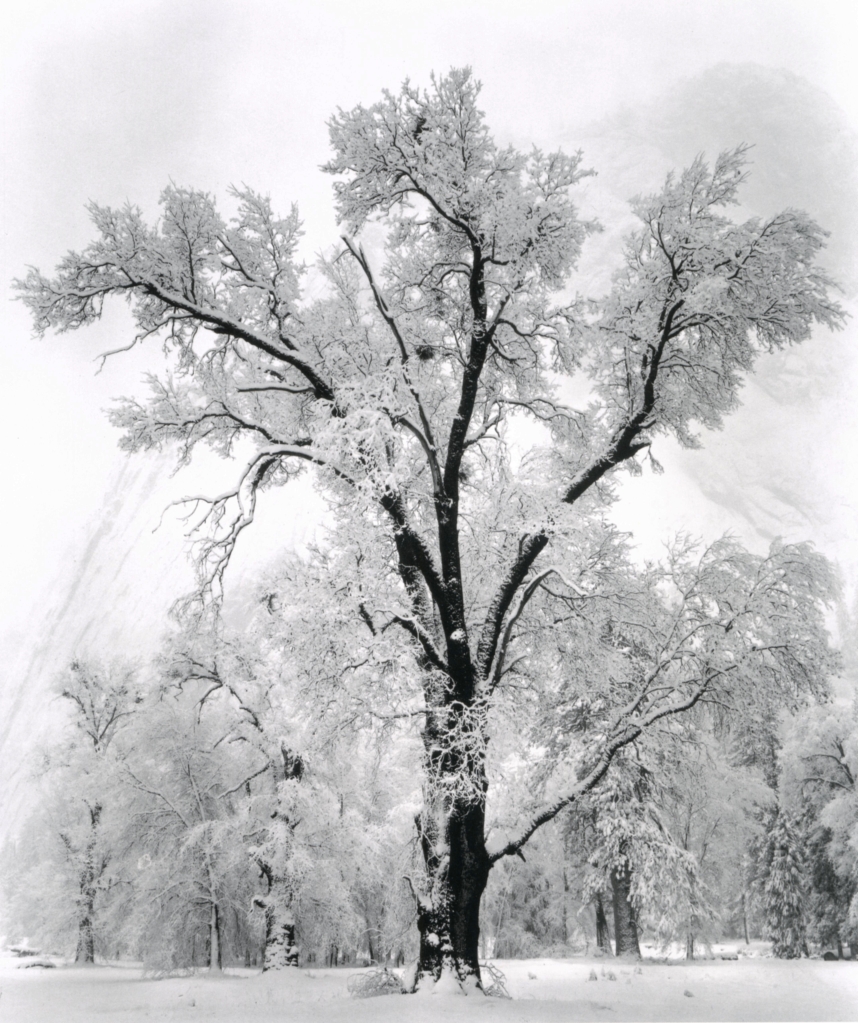

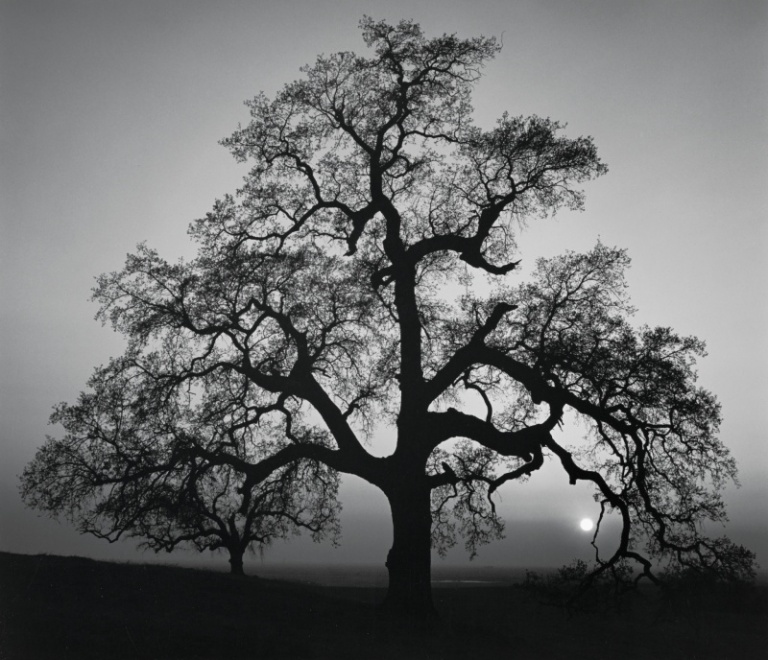

Yosemite

In the Spring of 1916, Ansel was confined to his bed with a bad cold. His Aunt Mary gave him a copy of the book, In the Heart of the Sierras by J. M. Hutchings. This changed Ansel’s life. It captured his very active imagination and became the headwaters of his obsession with Yosemite and the Sierras. He devoured every word and pored over every page many times. He became enthralled with the descriptions and illustrations of Yosemite and the romance and adventure within its peaks and valleys.[32] This obsession lasted over 70 years, resulting in more than twenty thousand photographs. It is by far the single largest body of work in his archive.[33]

Ansel first visited Yosemite in 1916, when he was fourteen years old. He later wrote, “I knew my destiny when I first experienced Yosemite. “Once he had explored Yosemite Valley, he began to hike and climb in the High Sierra—”my paradise,”as he called it.[34]

By 1916 Yosemite had been transformed into a vacation destination. When Ansel discovered Yosemite was only a two-day journey from home, he insisted that the family must visit “this paradise” which had so captured his imagination.[35] Ansel’s parents agreed, and plans were made. In Mary Street Alinder’s biography of Ansel, she gives this description of his first trip to Yosemite:

The train trip was a grand event for Ansel. The changing scenery enchanted him, from the grimy sections of the city to the rolling, grass-covered hills from which the train emerged into the great San Joaquin Valley. They disembarked in Merced and enjoyed a proper lunch at a hotel before boarding the Yosemite Valley Railroad, nicknamed the Shortline to Paradise, bound for El Portal, the gateway to Yosemite.

That night they spent at the luxurious Del Portal Hotel…. Ansel, awoke at dawn, bursting with impatience to board the large and completely open touring bus that would take them into the valley proper …. The rough gravel road climbed two thousand feet in ten miles. The bus rumbled along the banks of the Merced River, revealing little until they found themselves on the valley floor, turned a bend, pulled into a scenic turnout, and beheld Valley View. Ansel’s bright eyes flitted from wonder to wonder, but the impression that would last his lifetime was that of soaring gray granite cliffs.

The Adams family arrived at Camp Curry, were feather-dusted by the young staff, and greeted by the owner, David Curry, whose thunderous proclamation “Welcome to Camp Curry!” echoed off the close-by cliffs.[36]

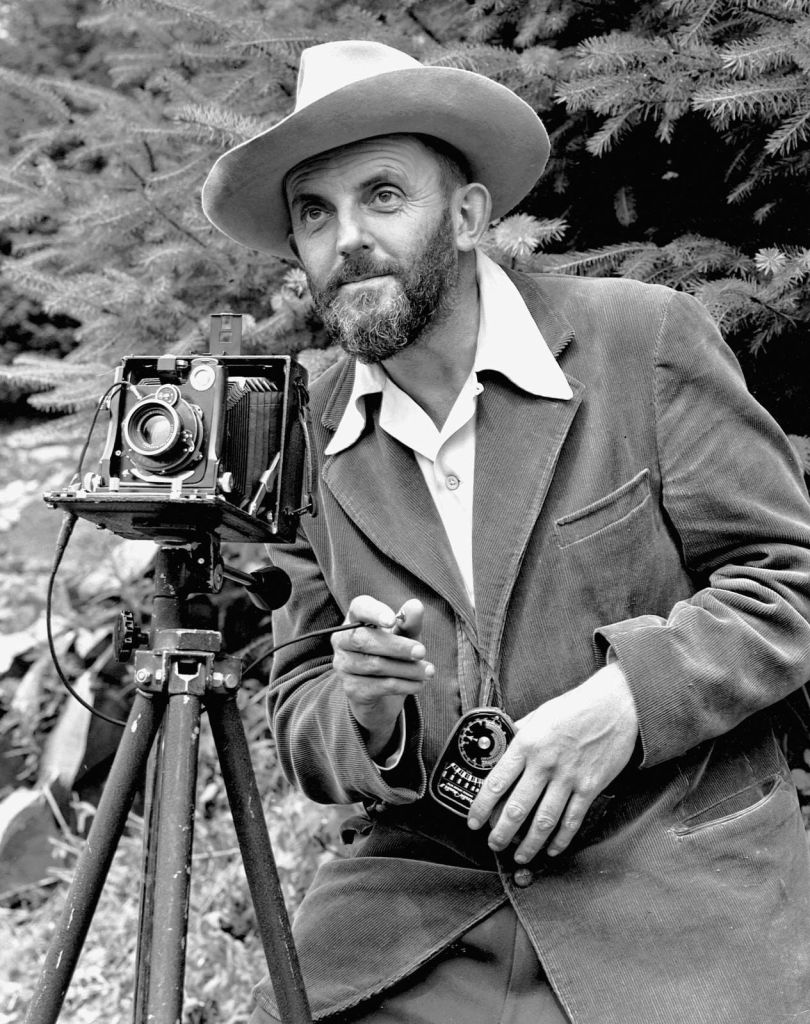

Shortly after their arrival, Ansel’s parents gave him his first camera, a Kodak No. 1 Brownie, which he took everywhere. The connection between Ansel, the camera, and Yosemite was immediate.[37] Little did Charles Adams realize that with this gift, he had set the course for his son’s life. Of these first pictures, Ansel said, “The results, photographically, were terrible, but the life bent and tempered something that I can never unbend and untemper in this existence—even if I wanted to.”[38]

The next year, Ansel and his mother returned to Yosemite. The year after that, he returned on his own. This began a yearly sojourn to “Paradise” for Ansel. Yosemite was now firmly ingrained in his soul and would have an enormous impact on his life. About his first trip, Mary Street Alinder said:

He hiked down the Tenaya Canyon and up the steep switchback trail to the top of Yosemite Falls, returning to camp hot and exhausted every afternoon to jump in the swimming pool. Although nearly friendless at home, at Yosemite he found playmates and learned to play croquet and pool. Upon his arrival in Yosemite, Ansel had been a sickly, fourteen-year-old; once there, he found health, happiness, and companionship.[39]

Early Photographic Education

After his adventures in Yosemite, the photography bug burned hot in Ansel. Camera stores, with their endless array of ingenious instruments, became a never-ending source of interest for Ansel. He began to devour photographic magazines and manuals; he attended one or two camera club meetings but found them boring.[40]

Shortly after returning home from Yosemite, Ansel got a job at a local photo-finishing business. Nancy Newhall, in her biography, The Eloquent Light, says:

A consuming desire to know all about photography seized Ansel. He walked two blocks up 24th Avenue and around the corner of California Street to Frank Dittman, whose photo-finishing lab turned out thousands of prints a day. “Please, Mr. Dittman, may I work for you? I don’t want any money. I just want to learn photography![41]

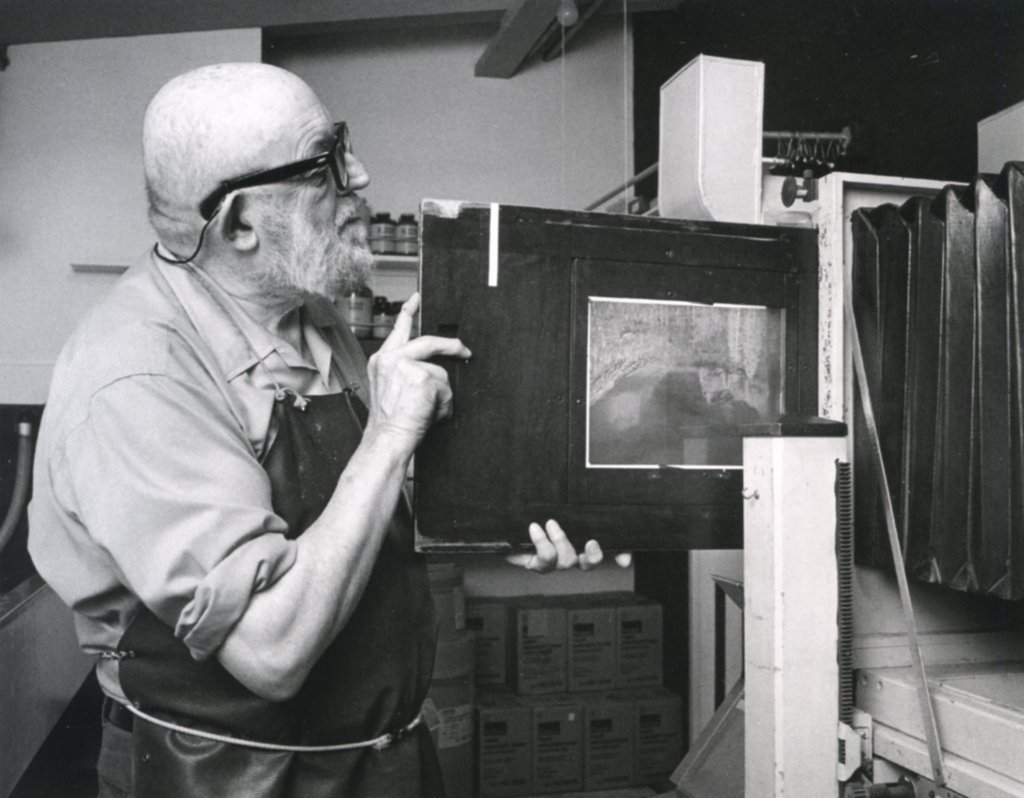

Ansel’s enthusiasm that day impressed Frank Dittman, and he hired Ansel as a “darkroom monkey,” paying him two dollars a day. As a darkroom monkey, Ansel would be out early delivering the previous day’s photographs and collecting the new film to be processed. He would arrive back at the shop around ten-thirty, where he either developed the new rolls of film or made prints from the preceding day’s collections. He learned his photographic routines quickly.[42]

Frank Dittman took Ansel under his wing and gave him a rudimentary photography education. Immediately Dittman recognized an inherent talent in the boy; I could see right off he was good.[43] In an interview he gave in 1950, Dittman gives us some insight into Ansel’s personality:

This lanky, beaky youngster with his long words, poetry, and enthusiasm for Yosemite, was a funny one. [His co-workers] called him “Ansel Yosemite Adams,” and they enjoyed teasing him. I noticed that he “never got mad,” he seemed to think the banter was funny, and “picked up cussing real fast.” He also noted that Ansel often played hooky from his music studies to work in his darkroom.[44]

After working in Dittman’s lab, Ansel was not a professional or creative photographer yet, but a dedicated hobbyist. He was still deeply immersed in music, and during the decade of the twenties, photography and hiking were his beloved diversions.[45] From my music studies, he applied the axiom of “practice makes perfect” to his photography. Mastering the craft of photography came through years of continued hard work, as did the ability to make images of personal expression slowly became part of his picture-making.[46]

At one of the early camera club meetings Ansel attended, he met W. E. Dassonville and saw the exquisite papers he sensitized for photographers to print on.[47] Dassonville, he learned, was a neighbor. Dropping in to see him now and then, Ansel absorbed the idea that photography could be an art.”[48]

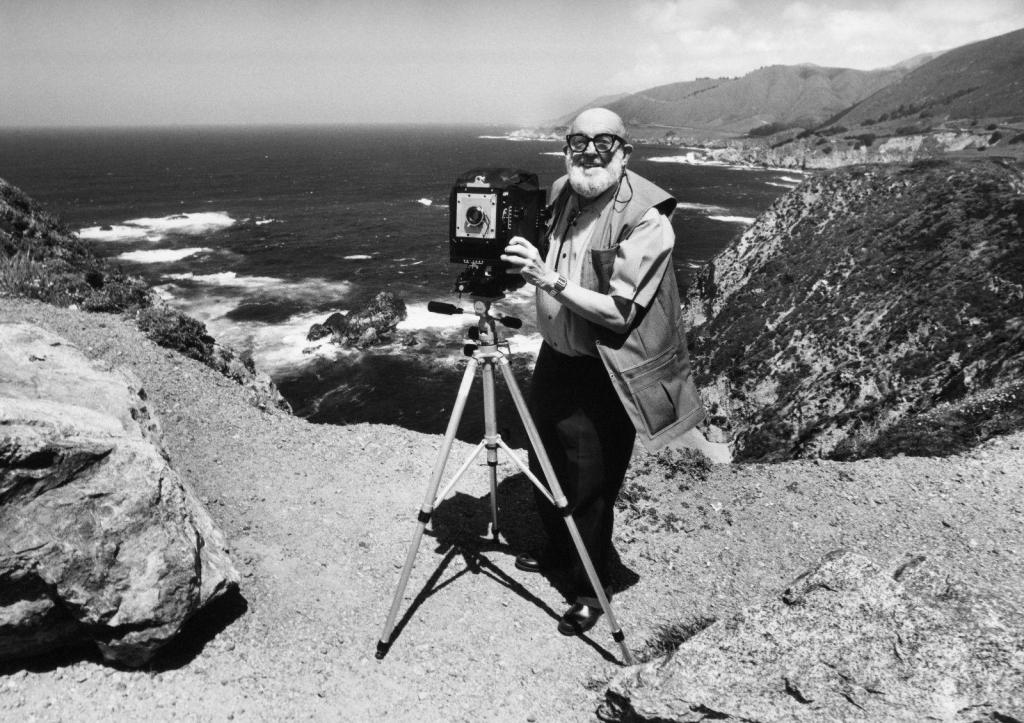

Photography

From his first day with a camera, Ansel took photography seriously. When he made his first exposure, a desire blossomed within him to improve. Up to his late 20s, photography was relegated to his summers in Yosemite; music was still the priority. Ansel came to believe that perfect photographic technique began with mastery of the camera and the picture-making process. Ansel’s photographs quickly progressed from simple shots of his family to images in which he took artistic pride.[49]

During the early part of the 20th century, Pictorialism was popular in photography. This was the style Ansel first tried to emulate. A popular criticism of the day was that photography was produced by a machine and not by an artist. Some photographers concluded that their prints must imitate “accepted” forms of art such as painting, drawing, or etching. Pictorialism was based on soft-focus, diffused light, and textured papers.[50] Mary Street Alinder said:

Ansel’s energies had been focused on the technical mastery of photography, but as he achieved that, he began thinking about the expressive potential of Pictorialism. Over the next four years, Ansel experimented with many aspects of photography, including making photographs through microscopes, telescopes, and soft-focus lenses. He tried out a variety of printing stock, from parchment-like sheets to matte-surfaced, golden-toned papers, and Bromoil papers. He began signing his prints, at first just “Adams,” but soon “Ansel Easton Adams” or “Ansel E. Adams,” with a curlicue-ending flourish.[51]

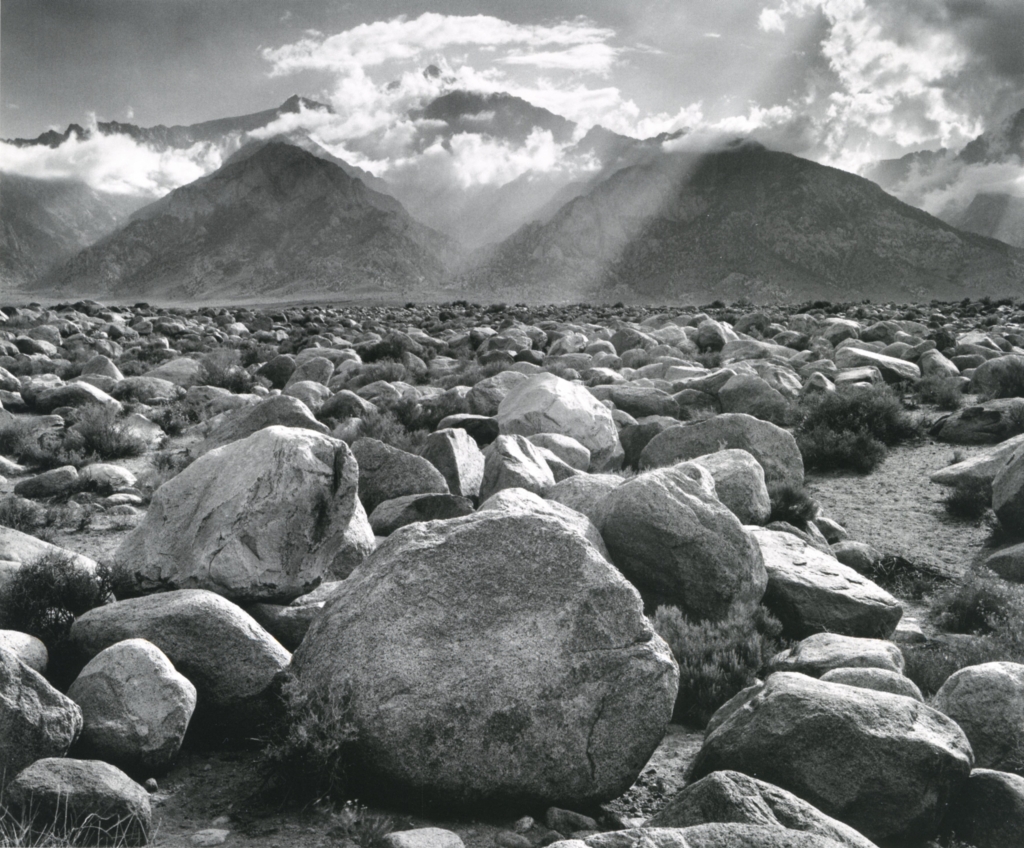

A glimpse of Ansel’s maturing vision can be seen in his first significant image, “Banner Peak and Thousand Island Lake”, of 1923. With a thunderstorm imminent, rolling clouds fill the sky above sculpted Banner Peak; Thousand Island Lake lies quietly at the mountain’s base, rimmed by a foreground of brush and boulders. Each element joins together to form the stronger whole of a dramatic picture. Although Ansel believed his soul was at one with the Sierra, he still could not reliably produce what he saw in a finished print. He always believed his early dramatic landscapes were accomplished by luck.[52]

With each passing year, Ansel’s approach to photography narrowed. In a letter written in September of 1923, he declared that from that day forward, he would seek to achieve the highest standards of art in his work, without compromise, and following purely photographic principles. Mary Street Alinder described his philosophy of pure photography:

What was Ansel’s definition of “purely photographic”? Primarily he meant no hand-coloring. Ansel prophetically proclaimed that black and white was photography’s true dominion. “Purely photographic” did not yet refer to the use of only photographic techniques, a restriction that he would come to embrace fully a few years later.[53]

By 1925, Ansel was quickly evolving from Pictorialism to straight photography. He decided that soft-focus and the textured papers were not appropriate for Yosemite’s sculptured granite. During this period of transition, Ansel took inspiration from the writings of English poet and philosopher Edward Carpenter. Ansel was introduced to Carpenter by his best friend, Cedric Wright.[54] Carpenter taught, “Never again will Art attain to its largest and best expressions until daily life itself once more is penetrated with beauty.” Carpenter’s teachings reaffirmed Ansel’s feeling that nature was the source of all goodness and man’s best friend, nourishing life by providing beauty. Cedric and Ansel made a pact: they would devote their lives to the creation of beauty. During the next few years, when he hiked and photographed the Sierra, Ansel always carried his pocket edition of Carpenter’s book Towards Democracy. [55]

Ansel’s final conversion to straight photography was completed with the images he made during the summer of 1925 while hiking with the LeConte family in Kings River Canyon. The result was a consistent group of sharply focused and cleanly composed images. Ansel declared that there was no looking back, and he was pledging his life to “Art.” His vision had narrowed so that the natural world appeared uncomplicated and understandable.[56]

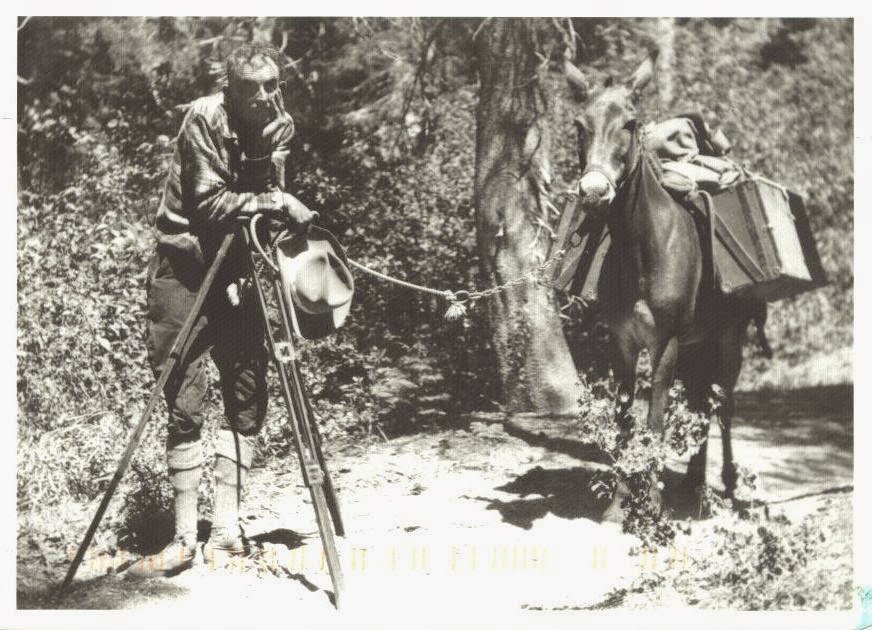

In the summer of 1917, when Ansel and his mother returned to Yosemite, Ansel enthusiastically began where he had left off the year before. For the first two weeks, he hiked 55 miles, and then it was 175 miles. His letters home regaled his father with his exploits and the wondrous adventures he was having. The letters from his mother tell a different story. Ansel was such a live wire that he was consuming all her strength controlling her rambunctious son, to the extent that she had to block the door of their tent at night with a chair to keep him from sneaking out.[57] Ansel was such a chatterbox that he soon became well known to everyone in camp.

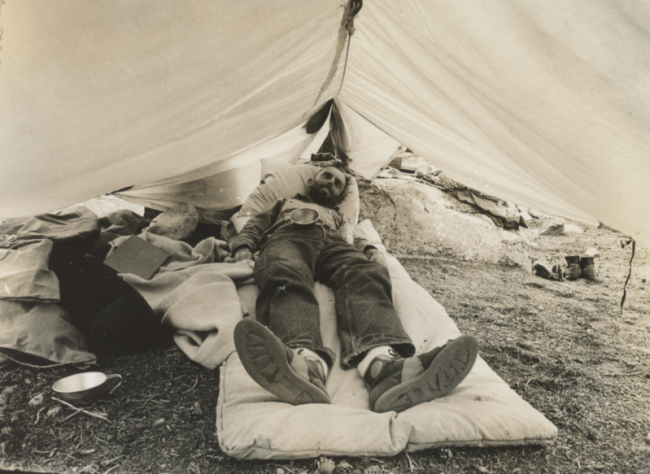

Uncle Frank

Francis Holman, an MIT graduate, a retired geologist, and an amateur ornithologist, invited Ansel on a camping trip to Merced Lake above Yosemite. This began an influential friendship that lasted many years. In his adult years, Ansel was considered an accomplished outdoorsman and environmental activist; this was largely due to the influence of Holman. Uncle Frank, as Ansel called him, became his guide to the outdoors; over the next few summers, he would teach his young charge camping, climbing, and serious respect for the fragile wilderness.[58] Ansel, in his autobiography, described his mentor:

His face was chiseled and sad, his mustache drooped. He had lost one eye in a firecracker accident when a child; the other eye was as sharp as an eagle’s. Uncle Frank knew the Yosemite Sierra well and was a genius of minimal equipment camping. He was a cautious climber, a productive fisherman, and a well-trained ornithologist, who installed in me a loathing for the killing of animals. He was a rigorous Puritan, kind, intelligent, though noncommunicative in ordinary things of the world. [59]

Ansel loved to tell stories, many of which were of his adventures with Uncle Frank hiking and camping in the Sierra; he said:

Uncle Frank and I had many marvelous and sometimes perilous experiences together in the Sierra. We rose from our sleeping bags at dawn and alternated the chores of our camp: preparing breakfast or going out into the frosty meadow and untying the burro. The ropes would be ice-hard, the knots congealed, and fingers aching and sore. In time I would get them loose and hear Uncle Frank yell, “For God’s sake, the mush is ready!” I would slowly struggle back, dragging one or two burros as the case might be, chilled to the bone, my legs wet and very cold, my nose runny, and my spirit dejected. I would soon revive, standing so close to the campfire.

Under the opposite situation, I would prepare breakfast: oatmeal (if any), bacon and eggs (if any), and flapjacks (always). Occasional trout brightened any cooked meal. We did not starve, but we would brush close to malnutrition. We never stopped to unpack for lunch, which usually consisted of dried fruit or whatever could be reached through the burro-pack covers. Dinner would be tinned meats and vegetables, sometimes canned soup, raisins, or dates for dessert, and maybe tea, especially if it was [cold]. The only thing I remember with distaste is that Uncle Frank was always determined to keep on the trail until it was practically dark. Then we would fumble for a campsite and a reasonably rock-less or pinecone-less stretch of flat earth.[60]

If Ansel were to write an epitaph of his friend, it would say, “Francis Holman gave more to the mountains than he ever took.”[61]

The next summer, sixteen-year-old Ansel went alone to Camp Curry. Ansel’s parents felt comfortable putting him under the watchful care of Uncle Frank and Jenny Curry.[62] The name Ansel Adams was now forever ingrained in the lore of Yosemite.

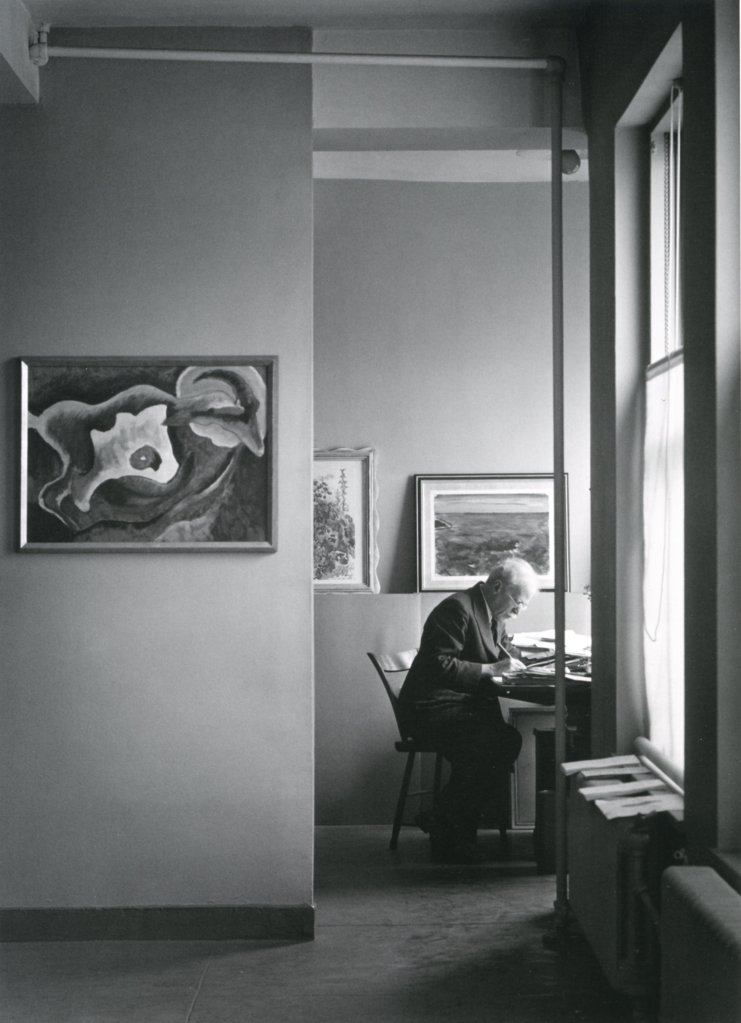

LeConte Lodge

In 1920 Ansel got a summer job at Yosemite. He was appointed the caretaker of the Sierra Club’s LeConte Memorial Lodge. The four summers Ansel worked at the lodge were magical. Ansel took his job seriously. He was responsible for building fires, looking after the collections of wildflowers, rocks, stumps, and cones gathering the latest information about the high country, and running errands in the club’s already ancient Model T Ford.[63] He slept in a tent in the meadow. He became a skilled climber. He was free to go out with his camera before the lodge opened; he was free again in the late afternoon.[64] Ansel would lead small groups on day trips around Yosemite. During these trips, he was introduced to the elite of the conservation world, many of whom would become life-long friends and fellow environmentalists. Notable among them were William E Colby[65]and Joseph N LeConte.[66] Ansel became very fond of the LeConte family.

Through the influence of Colby, LeConte, Uncle Frank, and many others, Ansel developed the skills and traits that would define his life and legacy. He became a dedicated and capable photographer, a fervent conservationist, and a skilled outdoorsman. Above it all, though, he longed for his piano. Even though Ansel was becoming a skilled photographer, his goal in life was still to become a professional musician.

Virginia Best

Yosemite posed one huge barrier for a young man aspiring to be a classical pianist. There was little opportunity for daily practice. Even a talented musician cannot take a three-month break each summer and expect to succeed. This dilemma was solved by park ranger Ansel Hall. Hall approached Harry Best, owner of Best’s Studio[67], and presented Ansel, saying, “here’s a namesake of mine,” and “he’d like to play your piano.”[68] Best graciously accepted this tall, awkward young man with the crooked nose, saying, “of course, he can come to play any time.” Harry Best thought that listening to Ansel’s play “was like listening to rippling waters.”[69]

Living with Harry Best was his seventeen-year-old daughter Virginia. Virginia was described as having “long fair hair, a delicate face, and very blue eyes. There was about her a warm simplicity and an affectionate radiance.”[70] In his autobiography, Ansel talks about Virginia:

I was first attracted to Mr. Best’s piano and soon thereafter to his seventeen-year-old daughter. Virginia Best was housekeeping for her father because her mother had passed away the year before. Virginia had a beautiful contralto voice and planned a career as a classical singer. We found considerable mutual interests in music, in Yosemite, and, it turned out, in each other.[71]

It was love at first sight for Ansel, but not Virginia. She said, “It took me quite a while before I realized that it wasn’t only the piano that brought him down to the [studio] … Because I just really wasn’t emotionally ready to get interested in anybody and didn’t believe anybody would be interested in me.”[72] For the first year, it was only a friendship, but after his return to Yosemite in 1921, their relationship grew beyond friendship.

While Ansel’s photography steadily progressed, his personal life was often a disaster. Ansel’s parents had a very formal marriage. They did not express their feelings with hugs or kisses; emotions were held at bay. Having no good model for a real-life relationship, Ansel worshipped idealized love, the purest of feelings above the physical plane. When he met Virginia Best in 1921, he saw her as good raw material and planned to mold her into his perfect woman.[73]

The summer of 1921 was a hectic time for Ansel. Things were heating up with Virginia; he was busy with his work at the lodge and preparing for his first extended trip in the High Sierra with Uncle Frank. The planned Itinerary included Merced Lake, Mount Clark, and the stunning area East of the Merced Mountains. Ansel would need to buy his own burro to help carry their gear and supplies. After the lodge closed in September 1921, Ansel, Uncle Frank, and the burro Mistletoe departed for high mountain valleys and the grandeur of the High Sierras. From high above Merced Lake, Ansel wrote Virginia:

This lofty valley and the grandeur of Rodgers Peak, the ascent of which is our main objective, cannot be described. If only I had a piano along! The absurdity of the idea does not prevent me from wishing, however. I certainly do miss the keyboard; as soon as I am back in Yosemite, I shall make a beeline for Best’s Studio, and bother your good father with uproarious scales and Debussian dissonances![74]

During their long winters apart, they wrote letters back and forth. Ansel would dwell too much on photography, and Virginia would remind him that his future was in music. She considered photography an unworthy use of his brilliant talents. Ansel reassured her that photography would remain nothing more than a hobby.

By the summer of 1923, Ansel and Virginia were in a good place together. Ansel was busy with the LeConte Lodge, photography, and his music studies. Virginia was busy taking care of her dad and working in the studio. They managed to find time together and considered themselves engaged, but no date was set.

In his autobiography Ansel wrote about his relationship with Virginia:

Virginia and I were serious for some six years before we were finally married in 1928. Engaged-disengaged-reengaged would be a more accurate description. A year after our first engagement, I realized how far I had to go with music before I would amount to anything, and I wrote her a letter of painful decision. Virginia took it wonderfully well, although I came to know later it was a most distressing event in her life.[75]

By the winter of 1923, Ansel’s love for Virginia had cooled. In a formal letter, he advised her that family and art came first, and he was duty-bound to assist his father as finances were uncertain. Not coincidentally, Ansel had recently begun his friendship with Cedric Wright. Through him and his Bohemian lifestyle in Berkeley, Ansel was meeting many other young artists and musicians, some of whom were students of his new friend, and some of them female.[76] Virginia must have seen this split coming, but it was terrible for her anyway.[77]

During the summers of 1924 and 1925, Ansel saw less of Virginia; he was invited to join Professor Joseph LeConte II and his family on six-week pack trips into the Kings River Sierra. Professor LeConte had been elected the second president of the Sierra Club. He assumed Ansel’s expenses in exchange for an album of his photographs of their sojourn.[78]

The fall of 1925 found Ansel back in San Francisco. He earned some money as a music teacher, offering ten lessons for ten dollars. He spent many nights at Cedric’s house in Berkeley. He formed the Milanvi Trio[79] but found little success; his music was dismally stalled. No one ever “discovered” him, and the future lost its promise. Over time, his disenchantment with the music scene increased until he finally dismissed it as unworthy of his involvement.[80]

Cedric Wright

Ansel’s best friend growing up was Cedric Wright. Ansel had first met Cedric briefly when he was eight years old.

Ansel did not see Cedric again until the summer of 1921, when both attended the annual Sierra Club outing. Cedric and Ansel became fast friends, finding they had many mutual interests, especially music, the mountains, and a budding interest in photography. Cedric influenced Ansel on many levels. Ansel was a regular at Cedric’s Berkeley home, where he met many of the people who were to become so important in his future years.[81]

Never wanting money, Cedric was a free spirit. He bought an old barn and hired famed architect Bernard Maybeck to design a craftsman-style renovation. Cedric’s house had built-in couches with loose pillows lining its walls and a swing hanging from the ceiling. [82]In her biography of Ansel, Mary Street Alinder wrote:

Ansel could often be found at Cedric’s home which became “party central” for Sierra Clubbers and musicians … Cedric entertained with ease, serving his guests what he believed to be the best chow in the world: the usual Sierra Club camp dinner of spaghetti and meatballs, French bread, tossed salad, and cookies supplemented with a treat of Jell-O for dessert. The coffee was boiled, thick, and rich. The only thing missing was the mountains.

Ansel idolized Cedric, whom he saw as intelligent, accomplished, and worldly. Cedric became his guide to the tantalizing world of wine, women, and song, and the young artistic achievers living in Berkeley.[83]

Ansel also had fond memories of Cedric:

I remember well the younger Cedric as almost an occupant of another world and a creator and messenger of beauty and mysteries. Perhaps his greatest gift was that of imparting confidence to those who were wavering on the edge of fear and indecision; often it was me. We shared much, playing music together, hiking together, writing letters with our deepest feelings, bolstering each other through topsy-turvy romances with dream girls and real girls.[84]

Cedric was greatly influenced by Walt Whitman, Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter, and Elbert Hubbard, whose doctrines of naturalistic simplicity especially captivated Cedric. Of all the poets and philosophers Ansel was exposed to, Edward Carpenter[85] had the greatest impact on his life. Mary Street Alinder wrote about Edward Carpenter:

[Edward]Carpenter’s beliefs reaffirmed Ansel’s feeling that nature was the source of all goodness and man’s best friend, nourishing life by providing beauty. An ordered nature conformed to an organic logic and pattern, but these largely eluded man’s comprehension. Nature was meaningful in a way that few could perceive, for one can seldom glimpse more than a small portion of the universal mysteries.[86]

Ansel’s goal, whether on the piano or through the camera, was to express what nature revealed to him. Through Cedric’s influence and others,[87] Ansel refined his life’s philosophy before he established its full expression through his art.[88] Mary Street Alinder said:

As the decade of the twenties progressed, Ansel’s attention focused less on music, and more on photography. It was difficult for him to keep up the charade of making music his life’s work when it meant spending long hours shackled to a piano in San Francisco. His mind wandered to the mountains as he sat at the piano, his fingers on the keys. Ansel’s siren and muse were Yosemite and the Sierra, not Bach and Beethoven.[89]

One early Spring Day Cedric Wright called to say, “Come over tonight and bring your earthquake nose, music fingers, and some prints to show.” After dinner, Cedric picked up my box of prints and led me to a smiling little man sitting on a couch. “Here’s Ansel Adams. He plays pretty good piano and takes damn good photographs.” Then to me, “This is Albert Bender. He lives in San Francisco, too, and he likes art.” I had heard of Albert Bender’s reputation as a serious patron of the arts. Albert stood, shook my hand, and said, “Let’s find some brighter light. I want to see your pictures.” Apprehensively, I followed him to a well-lit corner and watched as he carefully examined about forty of my photographs of Yosemite and the High Sierra. He finished, smiled, and said, “Fine! Come and see me at my office tomorrow morning at about ten. I want to look at these again.” I floated through the remainder of the evening – this was the first important interest in my photographs from someone outside my musical and mountaineering circles.

The next morning, promptly at ten o’clock, I was ushered into Albert’s office … His desk was a chaotic mess. He greeted me warmly, took me to a small table, pushed aside some books, and said, “Let’s look at them again.” After he finished, he looked me squarely in the eye and said, “We must do something with these photographs. How many of each can you print?” I replied, “An unlimited number unless I drop one of the glass plates.” He then said, “Let’s do a portfolio.” I remained outwardly calm but was electrified by his decision.

We quickly established the probable costs and the time required to do the job. He called Jean Chambers Moore,[91] a respected publisher, and dealer in fine books, and arranged for her to publish the portfolio and the Grabhorn Press to do the typography as well as the announcement. Edwin and Robert Grabhorn had developed a worldwide reputation for their incredibly beautiful typographic design and printing.[92]

At the same time, Ansel and Virginia were supposedly engaged, Ansel was madly in love with several of Cedric’s pupils. Despite all his wanderings, Virginia remained determined to marry Ansel.[90]

Albert Bender

In the Spring of 1926, Ansel’s fortune took a turn for the better. In his Autobiography, Ansel wrote:

Ansel and Albert decided upon an edition of one hundred portfolios (and ten artist’s copies) of eighteen prints each; Albert suggested a retail price of fifty dollars for each portfolio. Ansel continues:

Albert was a true philanthropist. He never requested money from his friends for any purpose unless he had first contributed. When he had concluded the arrangements for the portfolio, he said to me, “Of course, I’ll take ten copies. Here is my check for five hundred dollars.” He later bought ten more. He was back on the phone and, before lunchtime, with a magnificent job of promotion, he had sold more than half the portfolios, assuring the project’s financial success.

His first call was to Mrs. Sigmund Stern, who was kindly, wealthy, and always supportive of the arts. “Top of the morning to you, Rosalie! I have a young friend here who has done some fine photographs. We are going to make some portfolios and I have taken ten.” She said she would take ten, too. The same approach was used for several other benefactors of the arts, with considerable success.[93]

This was a momentous step for Ansel. The several thousand dollars he earned from the portfolios propelled him further toward a career with a camera, not a piano. In contrast, the piano generated only a few dollars an hour from lessons to neighborhood children. And, after an on-again-off-again engagement of six years, this money provided the financial security for him to marry Virginia Best.[94]

Albert’s generosity was legendary. His pockets were always full of small gifts that he gave out throughout his day; He loved helping people, be they janitors, esteemed authors, or photographers. In Ansel, Albert discovered a genius, a son, and an enchanting companion and could hardly wait to introduce him around. Ansel chauffeured Albert around in a 1926 Buick Coach that Albert owned. They made frequent grand tours to libraries, museums, and the studios and homes of many artists and writers. Albert would telephone Ansel and ask, “What are you doing today?” Ansel would reply, “When do you want to leave, Albert?” Practically every excursion was an important event to Ansel, for these were his introductions to a new world of creative people.[95]

The most memorable trip they took together was in 1927 to Santa Fe and Taos and the Grand Canyon. It was their first trip to the Deseret Southwest. It was nearly three thousand long miles, mostly on washboard roads.[96] Ansel was deeply moved by Santa Fe and Taos and quickly fell under the spell of the New Mexican light.[97]

Ansel was entranced by the old adobes, the Indian pueblos, the snow-capped Sangre de Cristo mountains, and the cosmopolitan world of artists and writers shown him by Albert. He took few pictures during this first trip, but when he returned the next year, he would be ready. Albert introduced Ansel to the writer Mary Austin, convinced that the two of them should collaborate on a book.[98]

Whether in New Mexico, Carmel, or San Francisco, Albert Bender opened many doors for Ansel throughout the years of their friendship. Although he was aware of his advancing age, Ansel took for granted that he would always be there. Virginia and Ansel were shocked to receive an emotional telegram on March 4, 1941, informing them that Albert had passed away after a short illness. Ansel describes the events of Albert’s death:

I thought of all Albert had been to me as we walked through the entrance garden to his door. Sandwiches, cookies, soft and hard drinks, and cheerful reminiscences softened an otherwise sorrowful occasion. Several people were there, some standing at the casket and others talking softly in the dining room. All during the wee hours’ men and women, singly or in couples, would enter the apartment quietly, many stricken with grief. Some talked about Albert and what kindnesses he had done for them; one elderly man whispered to me, “Albert helped put our son through college. We shall never forget him.” Practically all these people were unknown to me. Most were relatively obscure: clerks, nurses, gardeners, mailmen, garbage collectors, and janitors from his office building on California Street, and others who sought the last communion with their friend. These people of the night and dawn revealed to me the scope of Albert’s life. As I looked at Albert for the last time, seemingly comfortable in his casket and serene as if he were dreaming of his good works. His example of nobility and generosity bore fruit in many orchards of the human spirit.[99]

1927

1927 was a momentous year in Ansel’s life. With Albert’s influence, Ansel increasingly saw photography, rather than music, as his future.

In the spring, Ansel returned to Yosemite to the arms of the unspoiled, ever-patient, and welcoming Virginia. They traveled to Carmel for a brief getaway, during which Virginia was stricken with adoration. She discovered her own intense physical needs and yearned to be with Ansel all the time. Mary Street Alinder said:

For his part, Ansel seemed able to assume only one of two roles when relating to another: he was either the teacher or the student. He found only Virginia who was willing to put up with his endless lecturing on education, conduct, and discipline. For her part, Virginia coped in a passive-aggressive way, listening thoughtfully to everything he said and then doing pretty much as she wanted.[100]

Around the same time, Ansel made his first important, “visualized” photograph, “Monolith the Face of Half Dome” which is included in his first portfolio, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras [sic] which was also published that year.[101]

“Monolith, the Face of Half Dome“

Still hard at work on his first portfolio, Ansel knew he still didn’t have a photograph that communicated his true feelings for Yosemite. If anything can dominate that spectacular landscape, Half Dome does. He knew where he had to go.

In his book, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs Ansel describes the events of the day he made Monolith the Face of Half Dome:

At dawn, on a chill April 17 in 1927,[102] Virginia, two friends (Charlie Michael and Arnold Williams), and I began an eventful day of climbing and photographing. I had my 6.5 X 8.5 Korona View camera,[103] with two lenses, two filters, a rather heavy wooden tripod, and twelve Wratten Panchromatic glass plates.

We started up the chilly LeConte Gully. Ahead of us rose the long, continuously rising slope of the west shoulder of Half Dome. I had already made seven negatives by the time we reached the high area where the west shoulder meets the Dome. This is called the “Diving Board,” It is a great shelf of granite, slightly overhanging, and nearly 4000 feet above its base. [After arriving,] I made one photograph of Virginia standing on the brink of the rock ledge, a tiny figure in a vast landscape, and two other images of Yosemite Valley. I had two plates left – and the most exciting subject was awaiting me!

I turned to the face of Half Dome. When we arrived, it was in full shadow. By mid-afternoon, the sun was creeping upon it, I set up and composed my image. I did not have much space to move about in, an abyss was on my left, and rocks and brush on my right. I made my first exposure with plate number eleven, using a Wratten No. 8 (K2) yellow filter.

In my mind, I saw the photograph as a brooding form, with deep shadows and a distant sharp white peak against a dark sky. The only way I could represent this adequately was to use my deep red Wratten No. 29 filter, hoping it would produce the effect I visualized. I attached the filter with great care, inserted the plate holder, set the shutter, and pulled the slide. I knew I had an exceptional possibility in my grasp. I checked everything again, then pressed the shutter release for the 5-second exposure at f/22. After exposing the glass plate, I carefully inserted the slide and wrapped the plate holders in my focusing cloth for protection. We left down the west shoulder of Half Dome arriving home about dusk. I saw many gorgeous photographs on the way down but could do nothing about them, being out of plates.[104]

Mary Street Alinder, in her biography of Ansel, asks a very pertinent question about that day, she says:

Ansel confessed to ruining at least four of his twelve negatives that day through his own mistakes—overexposure, an ineptly placed plate holder, and blurred images from the unhappy combination of a stiff breeze and a telephoto lens fitted with a red filter that demanded a long exposure time. The entire purpose of that trip on that day was to make a picture of Half Dome worthy of his first portfolio. After so many sloppy technical errors, why did he approach Half Dome with only two remaining glass plates, unless he was completely confident of the image he was to make?[105]

“Monolith” is Ansel’s most significant photograph because he broke free from all photography that had come before with this image. Nothing in it smacks of Pictorialism, or Stieglitz, Strand, or Edward Weston.[106] This was a new vision, and it was his. He was now a true artist with a unique vision.

Within a month of making “Monolith”, Ansel had ceased all mention of a musical career. He had years of hard practice behind him, and it would be years before he could completely give up the idea of music. His whole life, Ansel enjoyed playing for his family and friends; that would be good enough.

Ten years later, Ansel came close to losing his negative of “Monolith” in a darkroom fire, Ansel tells the story:

I nearly lost this negative in my darkroom fire in 1937. On that occasion, Edward and Charis Weston, Ron Partridge, and I had just returned from a trip in the Minaret country south of Yosemite. We arrived in Yosemite in time for supper, but our evening of relaxation was disturbed by the fire. We were able to remove a good number of my negatives, but many early images were burned. We loaded the bathtub with wet negatives of all sizes, and glass plates at the bottom, and spent several days cleaning and drying them. It was quite a traumatic event! I never learned the cause of the fire, but it may have started in an old dry-mount press (without thermostat).

The negative was slightly damaged on the top and left-hand edge, and it is necessary to trim off about ‘/4 inches from each. Happily, the damage on the left is outside the trim area, but the loss at the top I could do without. Prints from before the fire show slightly more of the top edge of Half Dome. The negative is still printable, and I feel that my recent prints are far more revealing of mood and substance than are many of my earlier ones.[107]

Over the years, Ansel became increasingly aware of the importance of visualization. He dedicated his life to refining the concept. He always remembered the excitement of seeing his vision “come true.” This was one of the most exciting moments of his photographic career.[108]

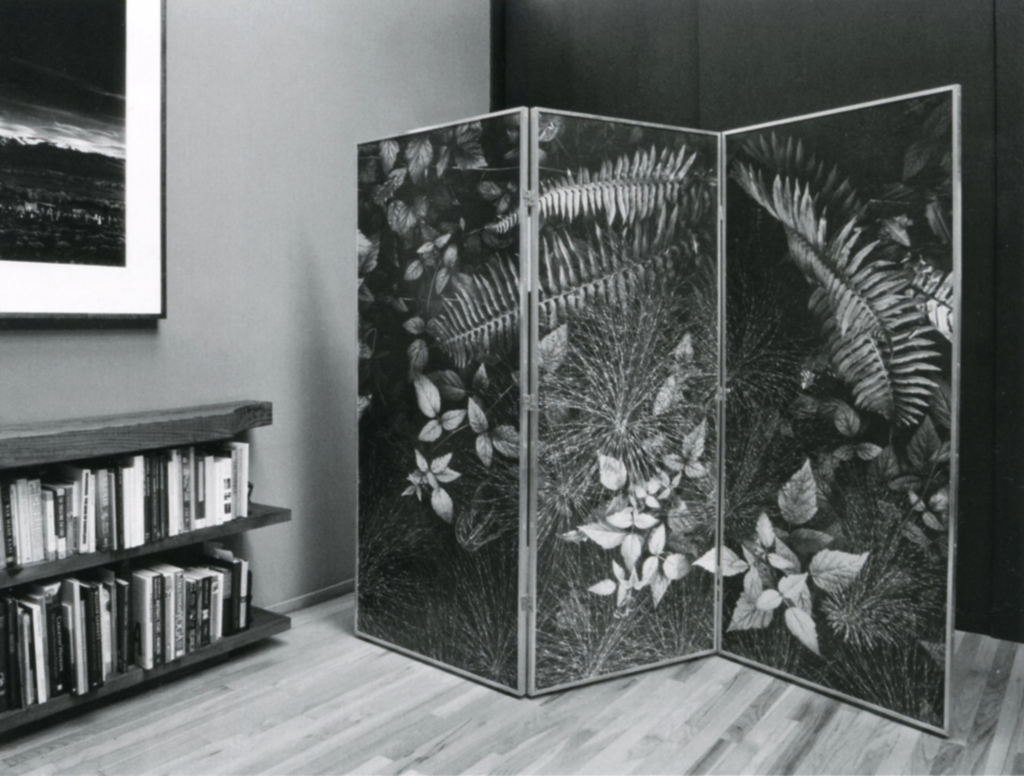

Portfolio One

During that momentous hike to the Diving Board, Ansel captured three photographs for his impending portfolio, “Monolith,” “Mount Galen Clark,” and the one of Virginia, entitled “On the Heights.” Mary Street Alinder said:

In addition to these three, Ansel selected fifteen other images for the portfolio, most made during his trips to the Kings River Canyon Sierra with the LeConte family. All were from glass plates, save one on film. By the late 1920s, Most photographers had switched to sheet film, but for several years to come Ansel would remain convinced that glass plates produced better negatives.[109]

The portfolio was, at last, taking shape. Black silk lined with gold satin was chosen for the portfolio covers, with the name embossed in gold on the front. A buff-colored, rough-textured, handmade paper folder encased each print, with the title typeset in black.[110]

Ansel later remembered:

He had completed about a hundred sets, some were destroyed in a warehouse fire, leaving approximately seventy-five that were sold and delivered. Their sale at fifty dollars apiece grossed him about $3,750, a handsome sum in 1927, even after the expenses of paper, processing, packaging, typography, and production were deducted. For those with less abundant finances, Ansel also offered individual Parmelian prints at five dollars apiece. Over the next three years, from the spring of 1927 to the spring of 1930, he sold 1,943 photographs.[111]

With the publication of Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras in August 1927, Ansel’s career as a photographer looked both viable and appealing. Now he could marry Virginia.

Marriage

Ansel had accumulated enough savings from the sales of Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras. With little notice, he, Cedric, and Dorothy Minty presented themselves at the Bests’ Yosemite door on December 26, 1927. Immediate marriage to Virginia had not been on Ansel’s mind, but Cedric had made it his earnest project and convinced his friend that the time was right. Ansel proposed, and Virginia accepted. Mary Street Alinder described the wedding day:

They were wed before eighteen guests in front of the fireplace at Best’s Studio at three in the afternoon on January 2, 1928. Attired in hiking clothes, Cedric served as best man and violinist Minty and pianist Ernst Bacon performed the third movement of a Cesar Franck sonata. With no chance to leave the valley to shop, Virginia was married in her best dress, which came from Paris but unfortunately was black. Certain this was a bad omen, Ansel’s mother wept. She and Charlie had brought the wedding ring, a gold band set with small diamonds, from San Francisco; Cedric had briefly lost it in the snow as he wrapped chains around the tires on Ansel’s car. Ansel wore the only pants he had brought – knickers – and his black basketball sneakers. Following a celebratory dinner, the newlyweds left with Cedric for Berkeley, where they spent their wedding night on a cold, uncomfortable single cot.[112]

Ansel had a plan: the first three years of their marriage would be devoted to the development of their respective arts. Hoping to save up enough money for their own home, they moved in with his parents,[113] where they stayed for the next two years.[114]

Ansel continued his traveling ways, leaving Virginia at home because they could not afford her costs, too. They wrote to each other frequently during his many absences. Her letters were adoring, while he repeatedly admonished her to improve herself and often scolded her for her lack of application.[115]

Dismissing Ansel’s plan, Virginia wanted first to establish a comfortable home for her man and to raise babies, but Ansel was in no rush to have children. He wanted his wife to be an equal, a companion, a liberated woman. He encouraged Virginia to look toward a music career, a goal that was opposite of Virginia’s dreams. The newlyweds seemed to be on different pages in life. The marriage of Ansel and Virginia was in trouble right from the start.[116]

Taos

In May 1927, Ansel drove Albert and his friend, the writer Bertha Damon, nearly three thousand miles to Santa Fe, Taos, and the Grand Canyon.[117] He didn’t photograph much that first trip, focusing more on developing a network of relationships that proved valuable in the future.

One of the most significant people Ansel met on this first trip was Mable Dodge Luhan. Mabel Gansen Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan was an art patroness, writer, and self-appointed savior of humanity.[118] She was a woman of profound contradictions. She was generous. She was petty. Domineering and endearing.[119] Mary invited some of the greatest minds of the 20th Century into her home,[120] where they were entertained, inspired, and free to go about their creative business. Notables that Ansel met through Mabel were John Marin (painter), Robinson Jeffers (poet), Georgia O’Keeffe (painter), Mary Austin (writer), and Paul Strand (photographer), among many others.

Ansel loved Northern New Mexico and the Southwest. He would travel back many times over the years to find inspiration and fresh subject matter.

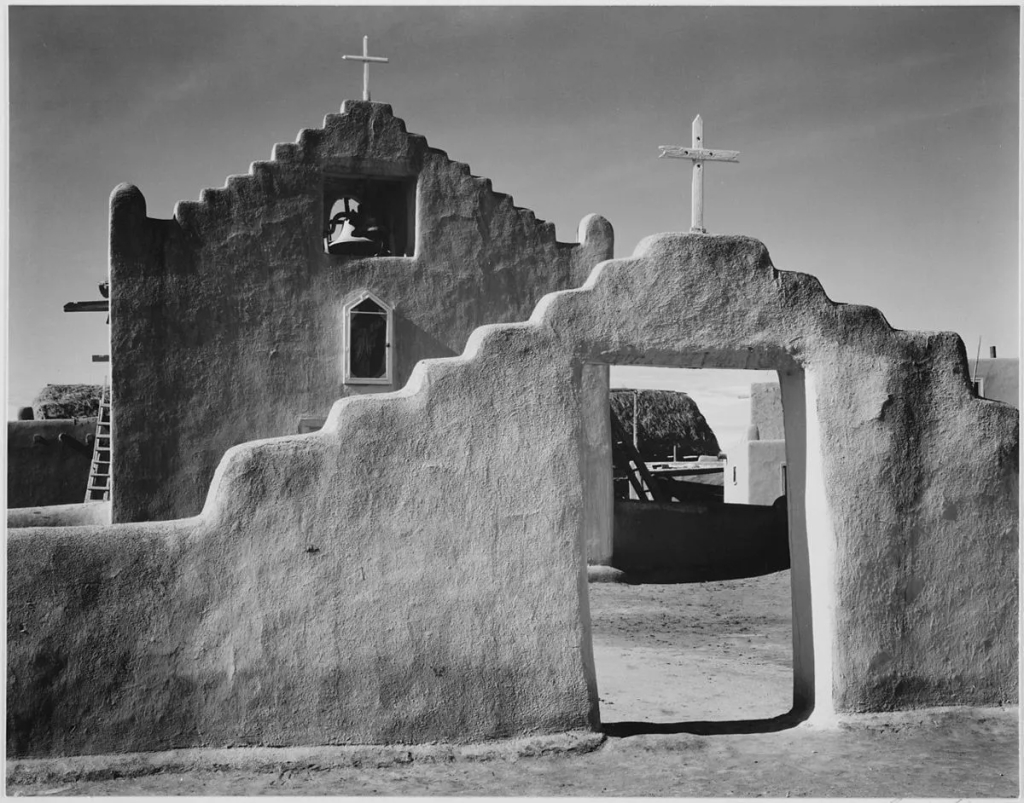

Taos Pueblo

In March 1929, Ansel and Virginia arrived on Mary Austin’s doorstep ready to begin work on the book.[121] Over the next few weeks, he explored and consulted with Mary Austin. He wrote Albert: “We have finally decided on the subject for the Portfolio. It will be the Pueblo of Taos.[122]

With Tony Lujan, a member of the tribal council, negotiating the terms, Ansel was given complete access to the pueblo for a fee of twenty-five dollars plus one copy of the finished book.[123] Ansel said, “The pueblo was open to me for as long as I needed to work, and I was permitted to return until I was finished with the project.” When the finished book was presented to the pueblo, it was carefully wrapped in deerskin and installed in one of the kivas.[124]

In Taos, Mabel Dodge Luhan (Tony Lujan’s wife)[125] graciously provided a guest room for Ansel and Virginia at her compound, Los Gallos.[126] When Ansel and Virginia were in Santa Fe, they stayed at the home of poet Witter Bynner where they partied every night.

During his time in New Mexico, Ansel photographed early and late, in good weather and bad. One day Ansel was doubled over in terrible pain, suffering from a ruptured appendix. Surgery and a two-week convalescence in Albuquerque returned him to health, and then it was back to Taos for an additional two weeks of photography. He and Virginia finally returned to San Francisco after three and a half months in New Mexico.[127]

The most significant image in Taos Pueblo is “Saint Francis Church Ranchos de Taos.” Called “Ranchos de Taos,” it is a strikingly beautiful image in its simplicity. It has been described as an “Experience in Light.”[128]

Of Ranchos de Taos, Ansel said:

I sensed the quality of light at the time but could not directly relate it to the photograph. Some intuitive thrust made this picture possible. I had used yellow filters (and red filters with panchromatic film) for many images in the area, but on this one occasion some gentle angel whispered, “no filter” and I obeyed. A darker sky would have depreciated the feeling of light. A more contrasty print also would have destroyed the inherent luminosity of the subject.[129]

Taos Pueblo was published in 1930, one year into the great depression. Albert took great interest in the project and offered to sponsor it. Albert again suggested they have the Grabhorn Press produce the typography and printing. Many weeks were required in the darkroom to make the nearly thirteen hundred prints. One hundred beautiful books (plus eight artist’s copies) with twelve original prints were produced. Albert set the price at seventy-five dollars each and, of course, took ten copies. The book sold out in two years. A copy of Taos Pueblo today brings around $85,000.[130]

Mary Street Alinder said this about Taos Pueblo:

Taos Pueblo is one of the most beautiful books published in the twentieth century. It is also the first and arguably the finest book of Ansel’s photographs ever produced, in part because it includes original photographs rather than photomechanical reproductions.’ He wrote to Mary Austin, “The book exceeds all my hopes for sheer beauty.”’[131]

Friends

Throughout his life, close friends influenced Ansel. Men like Cedric Wright, Uncle Frank, Albert Bender, Joseph LeConte Jr, and many more were the mentors of his youth. They molded Ansel into the man he was to become.

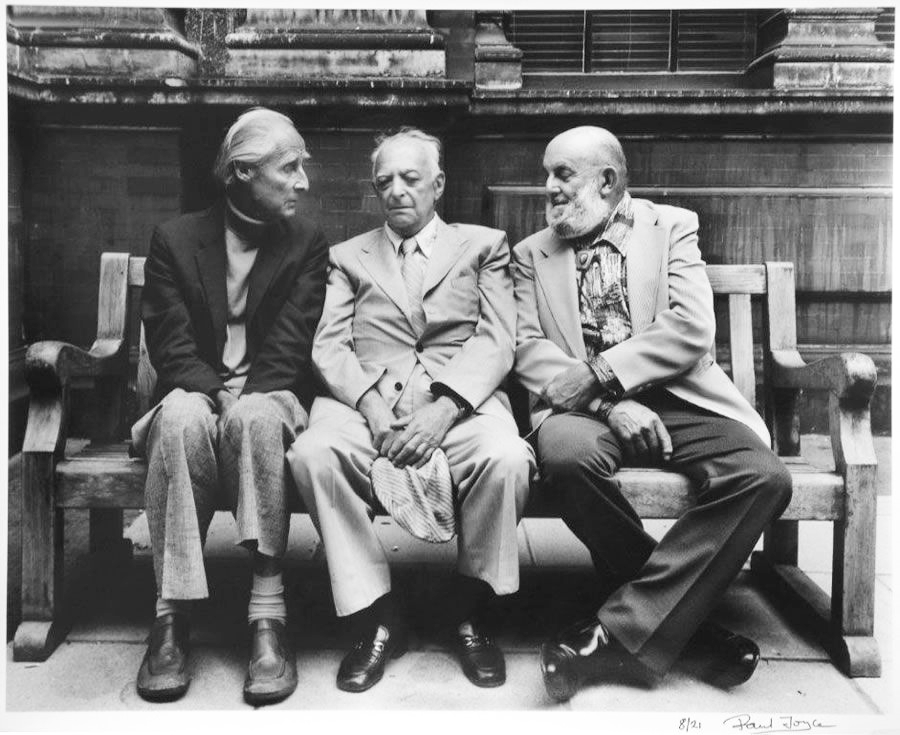

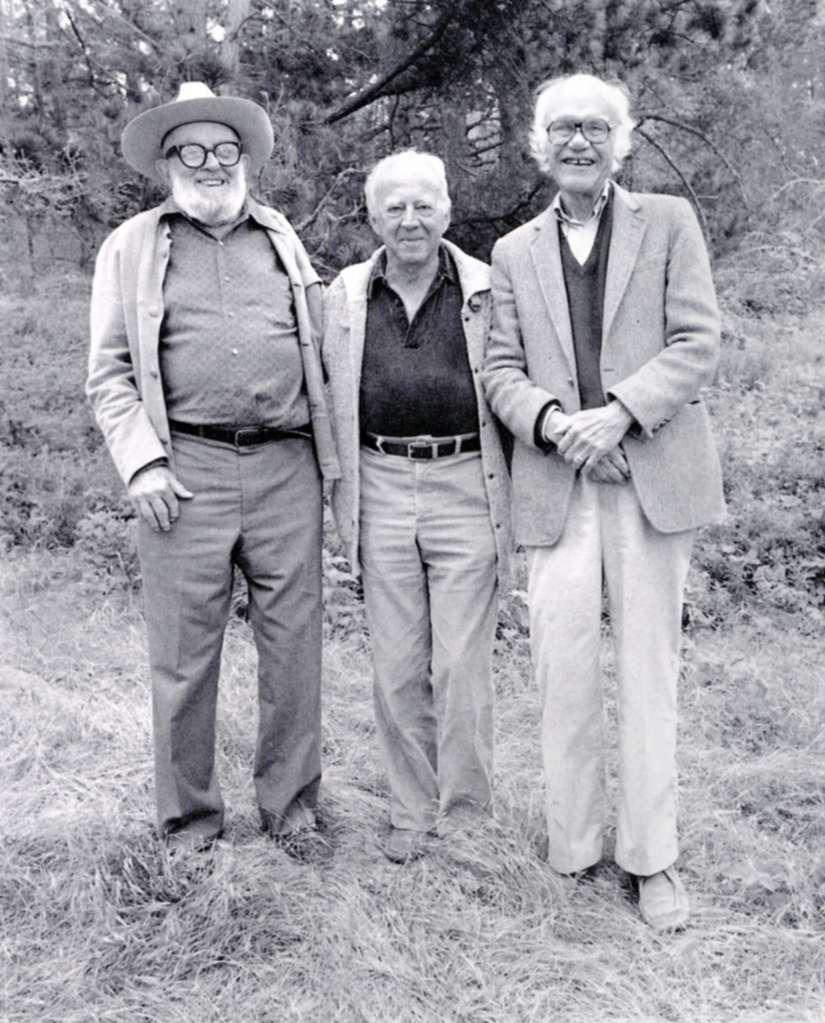

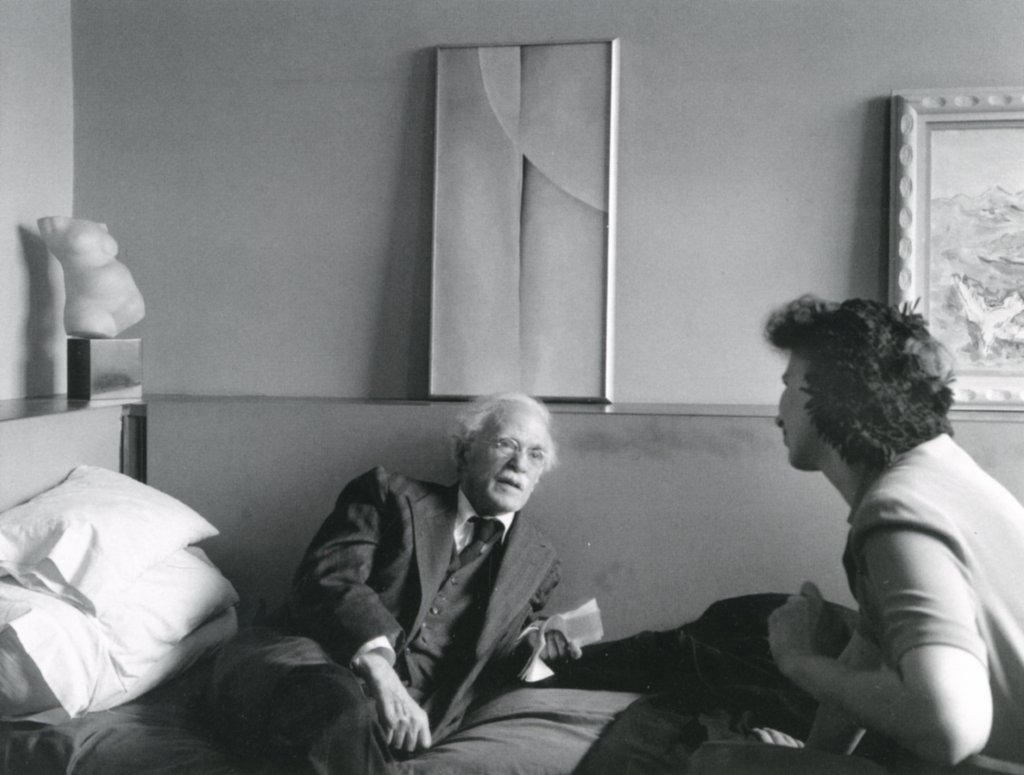

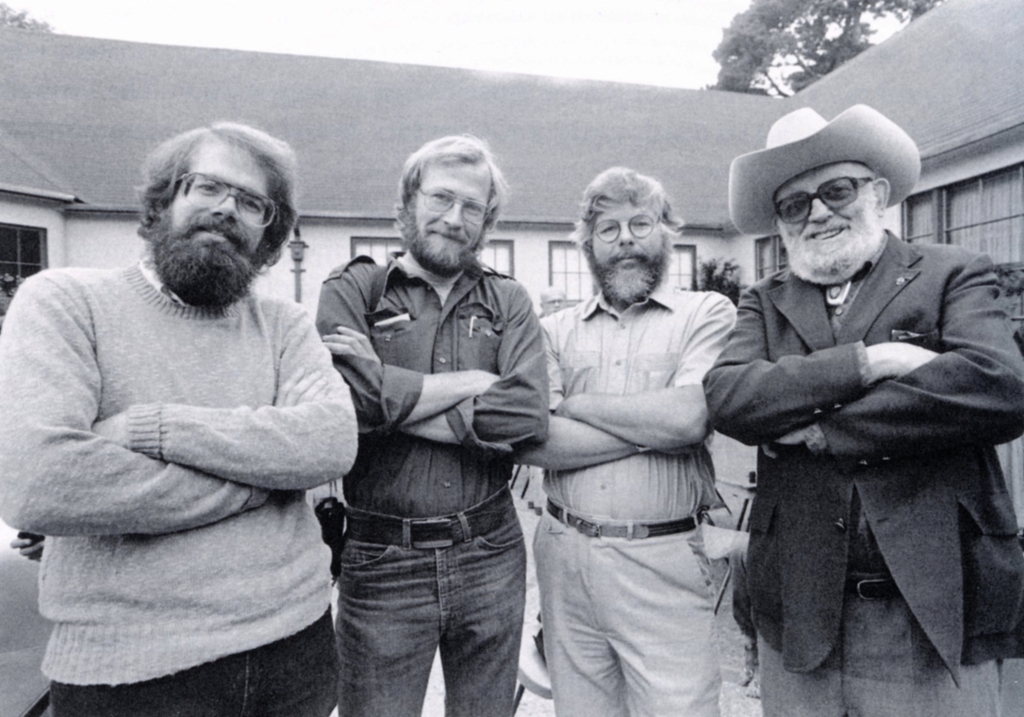

Later in life, Ansel was friends with most, if not all, of the inner circle of the photographic elite of the 20th Century. His closest friend was Edward Weston. Over the years, Ansel and Edward developed a strong respect for each other. He was also close friends with Imogene Cunningham and Dorothea Lange, who teased Ansel mercilessly. He took the ribbing with patience and good humor. Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz were his idols and close friends; Edward Steichen was his nemesis. Steichen was one photographer Ansel hated.

Over the years, he worked with Minor White, Willard Van Dyke, Brett and Cole Weston, John Sexton, Mary Ellen Mark, Ruth Bernhardt, and Margaret Bourke White. He consulted for Edward Land, Victor Hasselblad, and George Eastman. He met Henri Cartier Bresson, Brassai, and Man Ray in Europe.

The Friends of Photography held yearly workshops. Featured photographers that participated were Lee Friedlander, Emmet Gowin, Michael Kenna, Annie Leibovitz, Sally Mann, Duane Michals, and Arnold Newman. He was friends with W. Eugene Smith, Bernice Abbott, Bill Brandt, Wynn Bullock, Walker Evans, and Jaques Henri Lartigue. He met William Henry Jackson as an old man in New York, and he was photographed by Yousuf Karsh.

Ansel was also friends with many musicians, artists, and poets. Later in life, Ansel was close to his favorite pianist, Vladimir Ashkenazy. Called Vova by his friends, Ashkenazy was hired by Virginia and Mary Alinder to play a surprise concert for Ansel’s 80th birthday party.[132] Ansel was delighted with the gift. Vova was also scheduled to play a private concert for Ansel the day Ansel died.

His closest artist friends were painter Georgia O’Keefe, John Marin, and poet Robinson Jeffers.

His closest photo-related friends were Beaumont, Nancy Newhall, David McAlpin, and Mabel Dodge Luhan.

Although maybe not close friends,[133] Ansel was certainly aware of the work of photographers Alfred Eisenstaedt, Robert Cappa, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Lee Friedlander, Elliott Erwitt, Robert Frank, Gary Winogrand, Andre Kertesz, Vivian Maier, Robert Doisneau, and Herb Ritts.

Ansel knew the elite of the elite in the art world. Friends were very important to Ansel; they validated that he belonged in their world.

Paul Strand

With Taos Pueblo about to be published, Ansel returned to New Mexico to stay once again at Los Gallos. On this trip, Ansel shared a two-bedroom gatehouse with Paul and Becky Strand and Georgia O’Keeffe, whom he had met previously. That summer, Ansel’s discussions were primarily with Strand, the first serious photographer he had talked with extensively. Ansel knew that Strand’s photographs had been exhibited in New York and were admired by Alfred Stieglitz. Ansel gives us more detail:

Having brought no prints with him to Taos in 1930, Strand shared his recent negatives, all four by five inches. Placing him in front of a window and cautioning him to hold them only by their edges, slowly, one by one, Strand passed Ansel his precious sheets of film. Ansel was riveted, finding each exposure perfect and every composition ideal.”[134]

That summer with Paul Strand changed Ansel’s life. Strand revealed to him for the first time the full potential of photography. In discussing technique, Strand stressed the importance of glossy printing papers. Glossy papers rendered the qualities of each photograph better. Ansel became an immediate convert; Strand’s rationale was the catalyst that brought him fully into the straight-photography camp. In his autobiography, Ansel claimed that it was this exchange that caused him finally to commit to photography as a career.[135]

Group f/64

With Strand’s advice still echoing in his ears, Ansel began to print on glossy paper; he also changed his subject matter. He began photographing commonplace objects found around the docks and beaches of San Francisco.[136] His conversion to straight photography was almost complete; life was good for Ansel. After a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., Ansel was starting to be appreciated nationwide. He was now firmly established in the artistic elite of San Francisco.[137]

In 1932, craving community and a common desire to fight Pictorialism, seven of San Francisco’s photographic elite got together in Oakland, California, for a night of drinking. Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke[138], Henry Swift, Sonya Noskowiak, and John Paul Edwards, came together, to form a relationship and offer moral support in the fight against Pictorialism.[139] Ansel in his autobiography said:

We agreed with a passionate zeal to a group effort to stem the tides of oppressive pictorialism and to define what creative photography should be. On another evening at Willard’s, we bantered about what we should call ourselves. Picking up a pencil, I drew a curving f/64, representing the smallest and sharpest aperture on a lens, thus Group f/64 was born.[140]

Ansel continues his description:

The members of Group f/64 decided that our first goal would be to prepare a visual manifesto. Our work was varied but shared a fresh approach and perplexed many in the art world! This fresh approach delighted Lloyd Rollins, director of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco. Rollins had come to one of the gatherings at Willard’s where we had a small display of the group’s work. After looking at our photographs, he immediately offered us an exhibition. This was an important event for each of us; For this exhibition the seven members of Group f/64. invited four others to show with us: Preston Holder, Consuela Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, and Brett Weston, knowing that they represented the same photographic philosophy. A total of eighty photographs were in the show, from four to ten prints per photographer, with prices that now seem ridiculous: Edward charged fifteen dollars per print and the rest of us charged ten.[141]

The group handed out a written manifesto to accompany the visual one at the exhibit, it reads:

Manifesto

The name of this Group is derived from a diaphragm number of the photographic lens. It signifies to a large extent the qualities of clearness and definition of the photographic image which is an important element in the work of members of this Group.The chief object of the Group is to present in frequent shows what it considers the best contemporary photography of the West; in addition to showing the work of its members, it will include prints from other photographers who evidence tendencies in their work similar to that of the Group.

Group f/64 is not pretending to cover the entire spectrum of photography or to indicate through its selection of members any deprecating opinion of the photographers who are not included in its shows. There are a great number of serious workers in photography whose style and technique does not relate to the metier of the Group.

Group f/64 limits its members and invitational names to those workers who are striving to define photography as an art form by simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods. The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition, or idea, a derivative of any other art form. The production of the “Pictorialist,” on the other hand, indicates a devotion to principles of art whichch are directly related to painting and the graphic arts.

The members of Group f/64 believe that photography, as an art form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself.

The Group will appreciate information regarding any serious work in photography that has escaped its attention and is favorable towards establishing itself as a Forum of Modern Photography.[142]

Years later, Imogen Cunningham when asked who wrote the manifesto? She replied, “Ask Ansel. He must have written it. Nobody else would.”[143] For Ansel, the group “confirmed his ideas—seeing other work and ‘seeing’ for the first time. “He finally enjoyed and understood Edward Weston. The vibrations of the group increased my understanding and gave me confidence.” Willard Van Dyke recalled that as the youngest member, he found it “tremendously satisfying to come to Ansel Adams and Edward Weston and discuss prints—have them give [my work] serious consideration. Then Imogen Cunningham would make a wisecrack that would pare it right down.”[144]

Group f/64 was a landmark in the history of photography. It brought together photography’s most influential and important artists, all from diverse backgrounds, under one philosophical banner. Together they swore allegiance to the unmanipulated, straight print. They functioned together from 1932 until about 1940. Additional members were added over the years, the most significant being Dorothea Lange.[145]

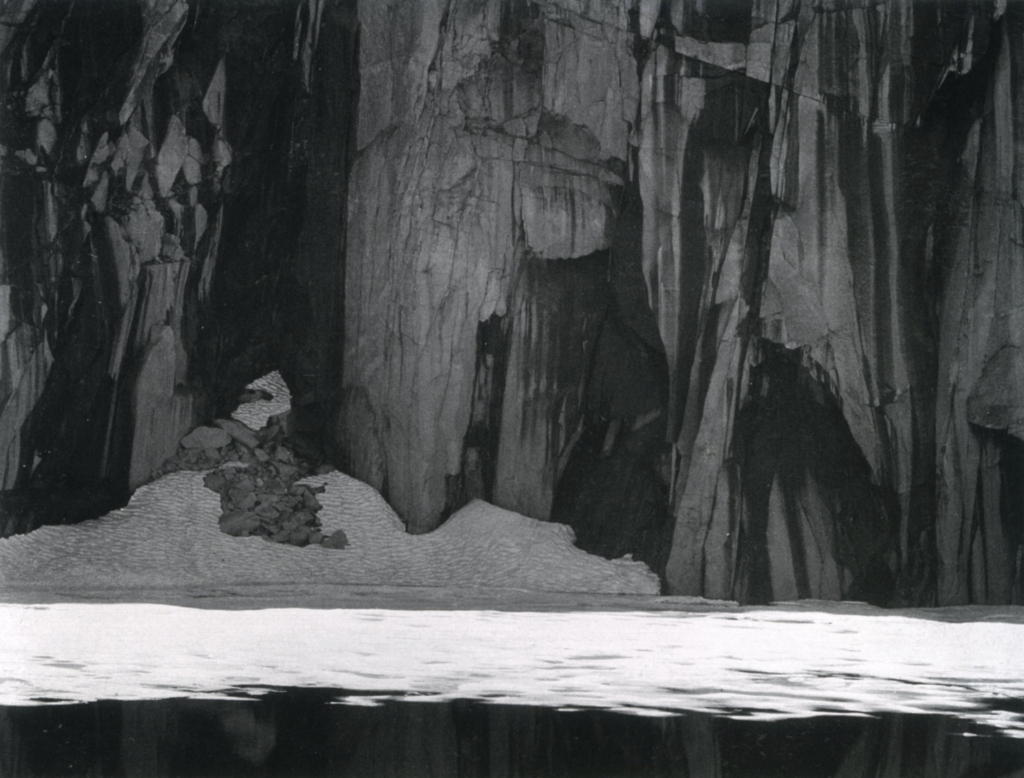

“Frozen Lake and Cliffs”

The most famous image Ansel displayed in that first Group f/64 exhibit was “Frozen Lake and Cliffs.” Taken on the 1932 Sierra Club Outing in Sequoia National Park,[146] “Frozen Lake and Cliffs” is considered a masterpiece and one of the earliest abstract photographs made directly from nature. Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, John Szarkowski, when talking about “Frozen Lake and Cliffs,” said, “This is not a landscape for picnics, or nature appreciation, but for testing of souls.”[147]

Alfred Stieglitz

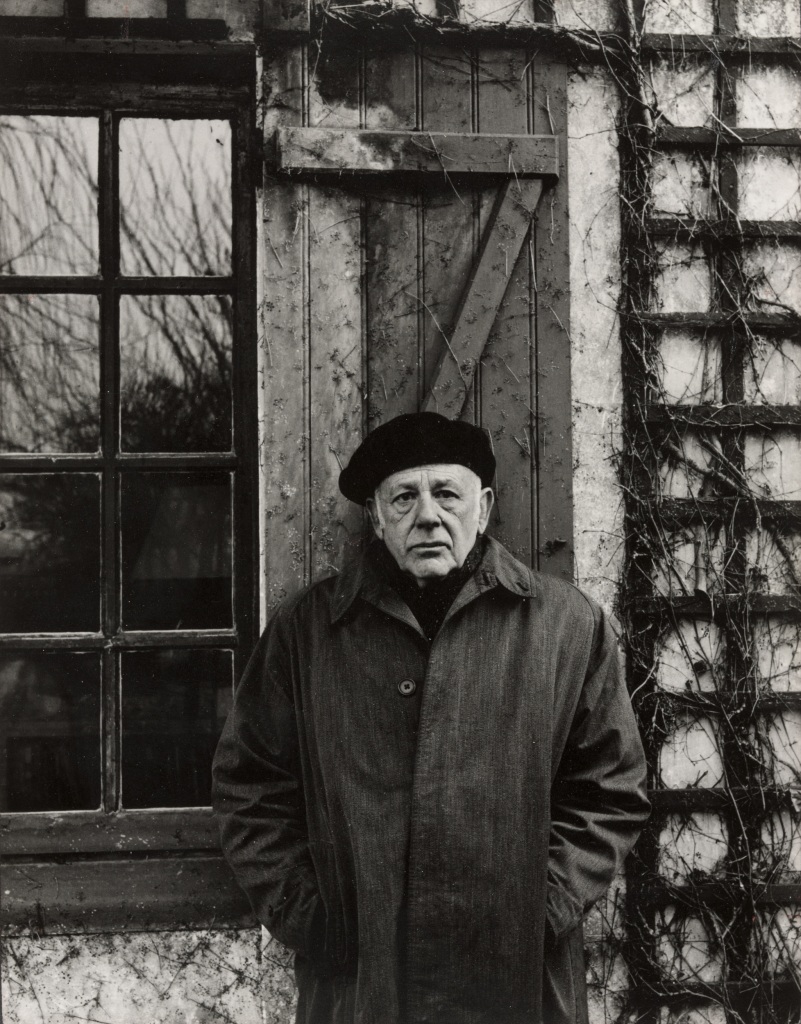

Ansel visited New York many times over his lifetime. He had a passion for the West, but the heart of the art world beat in New York. The main priority for visiting New York was to meet Alfred Stieglitz and show him his photographs.

Ansel met Stieglitz for the first time in 1933. Albert Bender suggested he set a priority to meet Stieglitz. Stieglitz had a well-earned reputation as a “curmudgeon who would not suffer fools—he was especially opinionated but… the chief man in America to have raised photography to a higher plane.” Ansel’s fellow photographers Paul Strand and Imogen Cunningham, and artists John Marin and Georgia O’Keeffe all advised Ansel, “Don’t fail to see him.”[148]

Mary Street Alinder tells the story:

They arrived in New York City on the morning of Tuesday, March 28. 1933. The weather was bleak, and the streets stank, piled high with garbage due to a strike. They found and rented an inexpensive studio at the Pickwick Arms Club Residence at a rate of sixteen dollars a week.After settling in, pregnant Virginia retired for a nap. Ansel took a brisk walk, then picked her up for lunch and a visit to the Museum of Modem Art (MoMA), followed by drinks and a Broadway show.

The next morning, leaving Virginia at the Pickwick Arms to unpack, Ansel charged off, intent on showing his photographs to Alfred Stieglitz at his gallery, An American Place. Composed of three galleries, a small office, and a storage room/darkroom on the seventeenth floor of an office building, Stieglitz founded An American Place in 1929…. An American Place attained an almost immediate status as an influential gallery that was sympathetic to artists—provided, of course, that the artist was deemed worthy by Stieglitz.

Ansel entered An American Place clutching a portfolio of prints (High Sierra landscapes and Group f/64 subjects), and a copy of Taos Pueblo. Stieglitz greeted him with a scowl, and a warning that he was too busy to be bothered, he allowed that if Ansel came back in a few hours, he might look at his work. Hopes dashed and offense taken Ansel huffed back to his room and advised Virginia that they were leaving the city.

Sensibly, Virginia insisted that Ansel give Stieglitz one more chance. His return visit to An American Place later that afternoon went even better than he could have dreamed. Bidding him sit down, Stieglitz took Ansel’s portfolio, untied the three black ribbons that held it shut, and slowly examined each print. There was only one chair in the gallery, and Stieglitz was sitting on it. Finding no other option, Ansel lowered himself onto the radiator. Whenever he tried to comment on one of the images, Stieglitz would glare him back into silence. Finally, Stieglitz tied the portfolio shut, paused, and then, with great thoughtfulness, untied it and began studying each print again. He gave the same careful attention to Taos Pueblo and expressed great appreciation for the elegant simplicity of both the design and the images … Stieglitz, with a direct look at Ansel, pronounced the work among the finest he had seen.[149]

Stieglitz came away from their meeting impressed by this Western man and his work. They were opposites, but each was committed to the art of photography. Although he did not offer Ansel an exhibition, Stieglitz urged him to write and visit whenever possible. Stieglitz’s theory of the equivalent helped Ansel’s photographic dreams take flight. Stieglitz promised that Ansel could discover more if only he would put his emotions into the creation of each photograph.[150]

From that first meeting, Ansel became Stieglitz’s devoted friend and follower. He believed that Stieglitz was one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century. He was inspired by and often repeated Stieglitz’s mantra: “I go out into the world. I take a photograph. I give it to you as the equivalent of what I saw and felt.”[151]

Ansel headed East in January 1936 to visit his friend in New York and attend a hearing in Washington DC. He wanted to show Stieglitz his more recent photographs. Ansel arrived with his portfolio in hand. Looking at his work, Stieglitz confirmed Ansel’s belief that he was making the best photographs of his life. After leaving him hanging for a few days, Stieglitz offered Ansel his long-sought show at An American Place in November. Ansel was overjoyed; planning for this event would be the focus of his entire year.[152]

Every negative used for the American Place exhibition had been taken during the previous five years. Four had been in the Group f/64 show, and most were in the Group f/64 style: close-ups of battered wood, cemetery stones, and rusted anchors. Ansel selected only pictures that Stieglitz had expressed a liking for. [153]

That November Ansel arrived in the city too late to visit the exhibition, but the next morning he entered An American Place and became transfixed by Stieglitz’s presentation, from the soft gray walls (a color selected by O’Keeffe) to the thoughtful sequencing of which images hung next to each other. Most were hung in a line, but a few were grouped in twos or threes, and a few were double hung, one above another. Ansel had achieved the pinnacle of success in the established art world.[154]

On one of his various trips to New York in the 1930s and 40s, he visited Alfred Stieglitz with his new Contax camera in hand. Ansel was sitting on a stool in the main gallery of An American Place and saw Stieglitz walking toward him. He quickly made an exposure. It happens to be one of the rare images of Stieglitz smiling. Stieglitz remarked, “If I had a camera like that, referring to the Contax, I would close this place up and be out on the streets of the city!”[155]